Robin Hood: Historical evidence in manuscript detailed by expert

When you subscribe we will use the information you provide to send you these newsletters.Sometimes they’ll include recommendations for other related newsletters or services we offer.Our Privacy Notice explains more about how we use your data, and your rights.You can unsubscribe at any time.

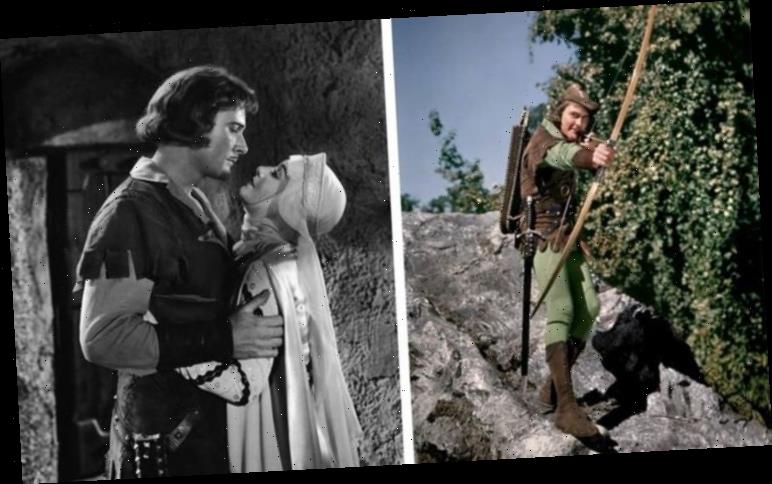

His heroic exploits inspired countless books, films and television series, portrayed on screen by stars from Douglas Fairbanks to Errol Flynn, Sean Connery to Kevin Costner, and Russell Crowe to Taron Egerton. Yet the 13th century outlaw – a questionable mixture of history and mythology – could easily have been forgotten and lost to the world forever, were it not for an obscure 18th century English adventurer who revived Robin’s memory and popularised the iconic champion of the common man we know today. Robin Hood had become a vanishing folk tale by 1795, when antiquarian Joseph Ritson of Stockton-on-Tees breathed fresh life into his legend.

“Without Ritson, Robin Hood could have faded into obscurity,” says historian Stephen Basdeo, author of the new book Discovering Robin Hood. “He was being forgotten, but Ritson invented the modern image of Robin Hood. If it wasn’t for Ritson we might not be watching Robin Hood movies today.”

It is thanks to Ritson that Hollywood versions portray Robin as a nobleman whose lands were seized by an evil King John, fighting to restore Richard the Lionheart to the throne, and stealing from the rich to give to the poor.

“Ritson created a Robin Hood to reflect his own prejudices,” says Basdeo, an associate professor at the Leeds campus of the Richmond University, barely an hour’s drive from Sherwood Forest.

“In the earliest poems and ballads about Robin Hood from the 14th century he was just a common or garden thief. He may have cared about the poor, but he never gave them any of the money he stole.

“It was Ritson, an ardent supporter of the French Revolution and its appeal for liberty, equality and fraternity, who transformed Robin Hood into a man of the people, giving his stolen wealth to the poor. Ritson made him the people’s hero, and that’s kept his legend alive.

“Ritson had travelled to Paris for several months during the French Revolution, and was deeply affected by what he saw there.”

The scholar returned to London filled with anti-monarchist fervour, and started calling friends “Citizen”. Buoyed by revolutionary zeal, Ritson imbued Robin Hood with socialist and egalitarian leanings, crediting the Medieval thief with the altruistic redistribution of wealth.

In doing so, he may have stopped the outlaw’s legend disappearing forever.

Ritson himself was a rags to riches story: a studious but often cantankerous academic who rose from humble Yorkshire beginnings to become a wealthy London lawyer. He traversed England gathering long-lost manuscripts of poems, ballads and songs telling the tale of Robin Hood, publishing a bestselling compilation in 1795 that revived interest in him as a valiant champion of the downtrodden.

Ritson discovered that Hood’s legend had become muddied over the centuries since his name first appeared in the 1370 poem Piers Plowman, and the earliest known tale of his adventures in Robin Hood and the Monk, composed around 1465.

“Robin Hood had become a rather inept outlaw by the time of 17th century ballads,” says Basdeo. “He was portrayed as a bit of an idiot, a clown who never did anything heroic, often beaten up by a stranger in a forest. By Ritson’s day Robin Hood was largely forgotten, and if he appeared at all it was only as a buffoon in cheap songs crafted for the lower classes.”

Ritson’s 1795 biography, mingling dubious history with rumours, changed all that, transforming the bumbling outlaw into an action hero. “He took a comic figure and lowly thief, and fundamentally reshaped him into that of a heroic revolutionary freedom fighter,” says Basdeo.

“Ritson gave the world the image of Robin Hood which has persisted in so many retellings right through to the 21st century.”

Defiantly atheist, Ritson emphasized Robin’s delight in stealing from corrupt and immoral priests, monks, abbots, bishops and clergy. And though early texts clearly portrayed him as a yeoman – neither an aristocrat nor peasant – the upwardly-mobile Ritson favoured the legend that had elevated the outlaw to the peerage, at least toward the end of his life.

“His alleged nobility became a historical ‘fact’ because of its tentative inclusion in Ritson’s book,” says Basdeo. “Being the first Hood biography of Robin Hood, it became the definitive version. Yet there’s a debate as to whether Robin Hood even existed, which continues to this day.”

While some modern scholars believe him to be merely a fictional creation, Basdeo notes that an outlaw named Robin Hood is listed as a “fugitive” in the York Assize Rolls for the years 1225-26.

According to Ritson, Robin Hood was born in Locksley in the county of Nottinghamshire around 1160. “His extraction was noble and his true name was Robert Fitzooth? He is frequently styled, and commonly reputed to have been, Earl of Huntingdon.”

After a wild youth, Robin’s “inheritance being consumed or forfeited by his excesses, and his person outlawed for debt, either from necessity or choice, he sought an asylum in the woods and forests,” ranging in Sherwood Forest in Nottinghamshire and Barnsdale Forest in Yorkshire, wrote the antiquarian.

“Ritson got a few things wrong,” admits Basdeo.

“There’s no evidence that he was Robert Fitzooth, or titled nobility. The Earl of Huntington is fictional, lifted from a 16th century play.”

Yet Ritson’s version of a gallant Robin Hood has inspired writers and filmmakers for more than two centuries.

The classic 1819 novel Ivanhoe, by Ritson’s good friend, Walter Scott, was directly inspired by the scholar’s reinvention of the Medieval outlaw. It also led to the mistaken belief that Robin Hood joined the Third Crusade with King Richard I and returned to England to find his estates seized by a rapacious King John.

“That’s a Hollywood invention borrowed from Ivanhoe, and we only have Ritson to blame for that,” says Basdeo.

The band of Merry Men is also a motley crew of doubtful historicity.

The earliest poems and ballads mention Little John and Will Scarlet, but the epicurean monk Friar Tuck, minstrel Alan-a-Dale, and Robin’s love interest Maid Marian – borrowed from a completely different French folktale – were all much later additions to the legend.

Early manuscripts also placed Robin Hood in the era of King Edward I, but later ballads dated his adventures a century earlier to the time of Richard the Lionheart.

Ritson’s book raised Robin Hood from obscurity, making him a household name in the 19th century, yet his own reputation followed the opposite path, as the antiquarian suffered a humiliating fall from grace.

His health had been deteriorating for some years, and within months of publishing his Robin Hood masterpiece he began to show signs of mental illness.

His wealth soon dissipated, and by 1803 he suffered a complete psychological breakdown, barricaded himself inside his chambers at Gray’s Inn and set his manuscripts ablaze.

Ritson was spirited away to a private lunatic asylum in Hoxton in London’s East End, where he died days later.

“It was quite a sad and painful demise,” says Basdeo. “He was able to save Robin Hood, but he couldn’t save himself.”

Discovering Robin Hood: The Life of Joseph Ritson – Gentleman, Scholar and Revolutionary by Stephen Basdeo (Pen & Sword History, £19.99) is published on March 31.

To pre-order with free UK delivery call Express Bookshop on 01872 562310 or order via expressbookshop.co.uk

Source: Read Full Article