Over the past decade, women have gradually embraced living their lives sheathed in spandex. The shift from so-called "real clothes" to athleisure has long been a polarizing one, with critics lamenting both our collective dressing down and the fact that wardrobe staples like workout leggings hug the body so tightly we might as well be walking around naked. "We may be able to conquer the world wearing spandex," an opinion editor wrote in The New York Times in 2018, "But wouldn't it be easier to do so in pants that don't threaten to show every dimple and roll in every woman over 30?" Rude.

Given the tenor of that criticism, the story of how workout wear became street fashion is a surprisingly feminist one. It's a story of women ditching their girdles and so-called "ladylike" attire in favor of comfort and freedom of movement, and it reveals a profound evolution not only in the way women move through their lives, but also in how we think about our own bodies. And it traces back to Gilda Marx, an ambitious aerobics instructor to the stars, who almost single-handedly launched the leotard dress code of the 1980s.

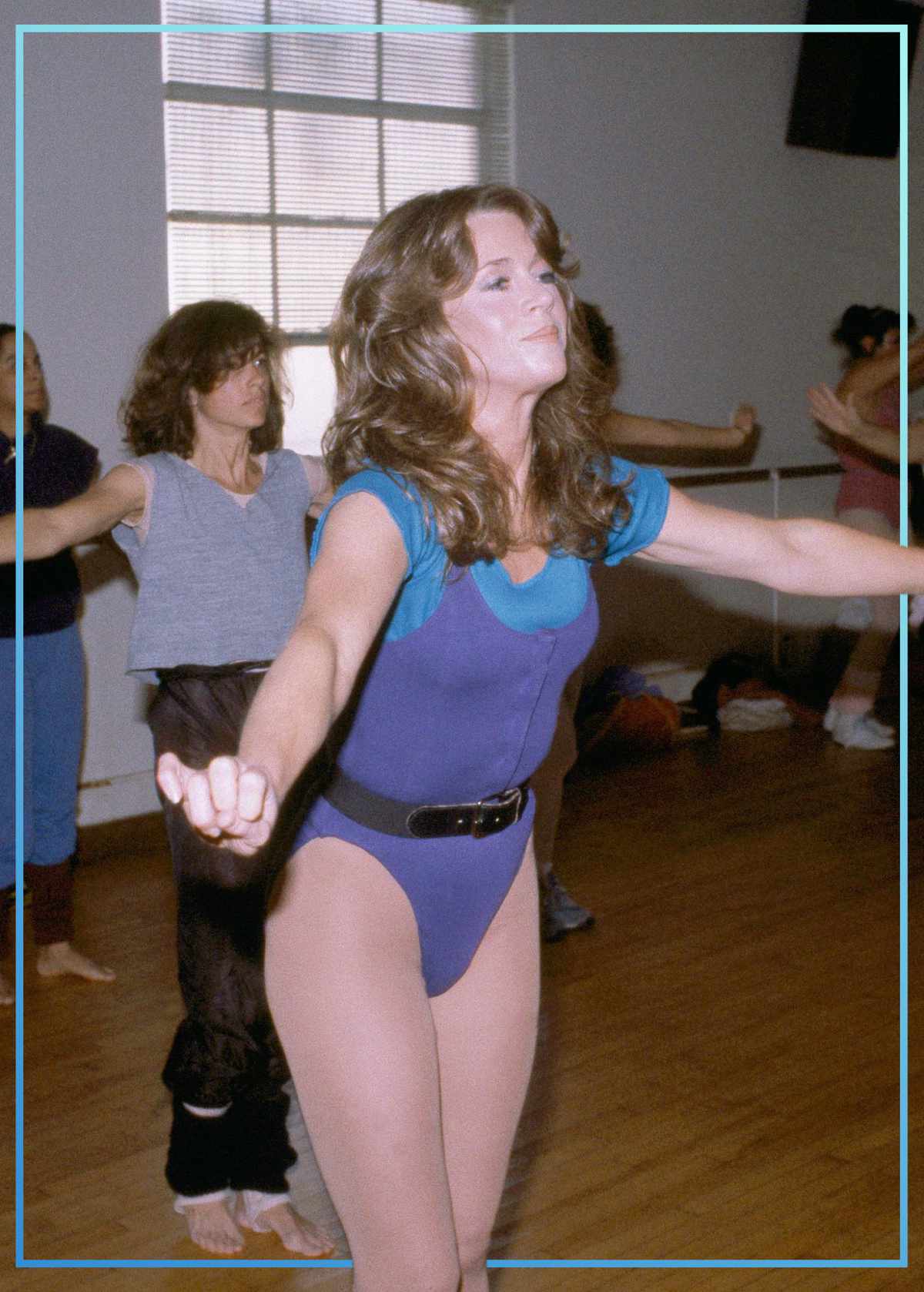

In the mid-1970s, while Jazzercise and small studios across America were bringing aerobic dancing to the masses, Gilda was teaching her own version of dance fitness to Hollywood's elite at Body Design by Gilda, a penthouse studio in Los Angeles painted shades of peach and blue. (Think Body by Bunny from Apple TV's Physical, but much more LA.)

Gilda attracted A-listers from Bette Midler to Barbra Streisand, who paid homage to Gilda in the 1979 romantic comedy The Main Event with a campy workout scene shot at the studio. "There were some classes where it was almost like a meeting of the gods," studio manager and instructor Ken Alan told me. "You know, the two biggest names in movies would be three feet from each other." Gilda's studio even launched the queen of fitness herself: Jane Fonda became hooked on its group classes in the late '70s; by '82 she had opened her own workout studio and released a mega-bestselling fitness book and home video.

But Gilda's influence would extend far beyond the rich and famous when she embarked on a quest to transform the era's universal exercise uniform. She wanted to build a better leotard.

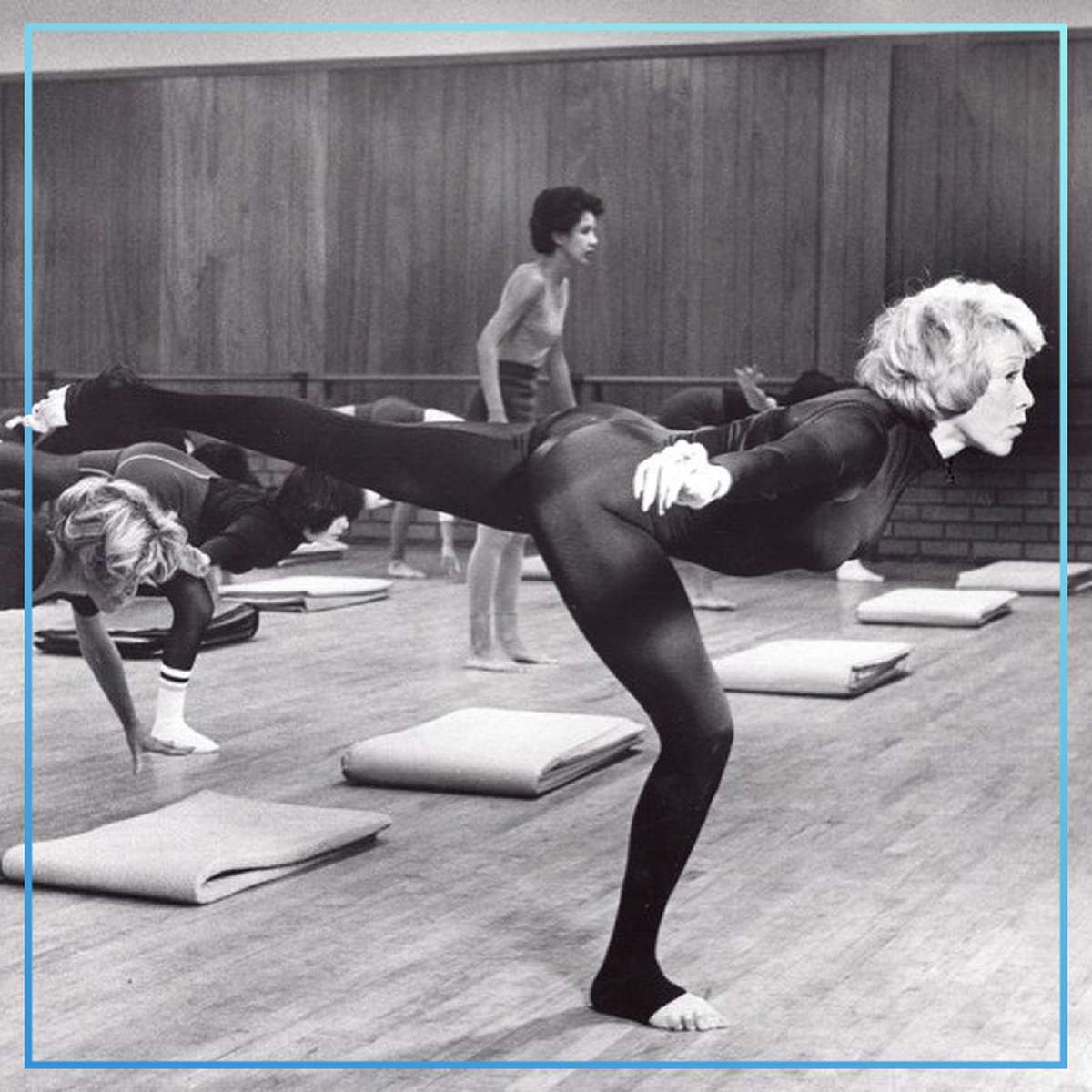

As someone who spent most of her time in leotards (she was a professional dancer before taking up aerobics), Gilda appreciated how they moved. But it bugged her that, for anyone who wasn't built like a prepubescent ballerina, leotards weren't always flattering — or comfortable. The garment hadn't changed all that much since its introduction by French acrobat Jules Léotard in the 19th century. By the 1930s, leotards dyed pink or black were dancers' rehearsal outfit of choice. But the leotards of mid-century America were still made of natural fiber blends, which meant they rode up in places they should stay down and sagged in places they should stay up.

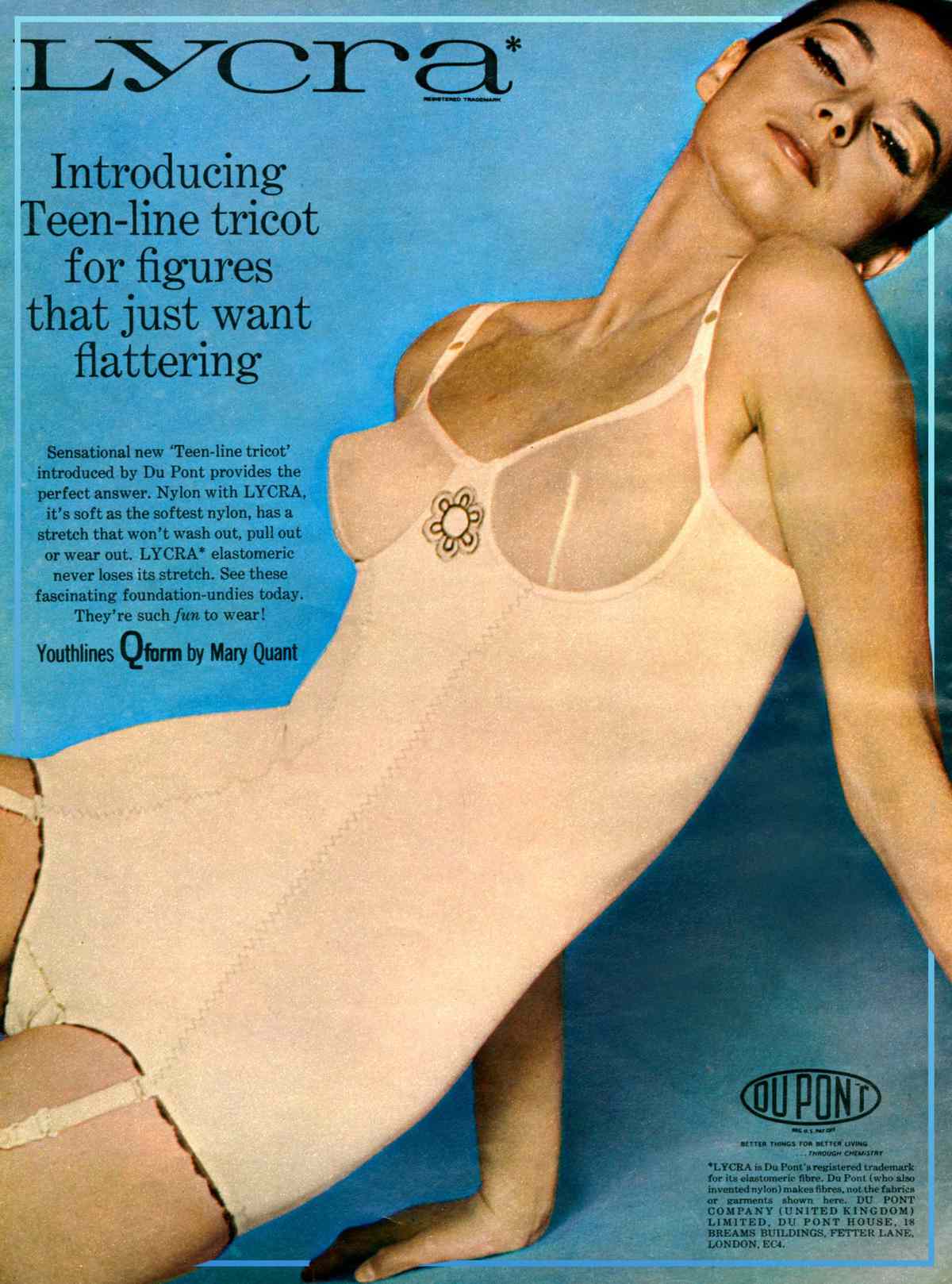

Gilda knew there had to be a better design, one that supported, flattered, and fit properly. "I wanted to create a beautiful garment that would inspire my students to want to exercise," she wrote in her 1984 exercise book, Body by Gilda. One that was "flexible, functional and fantastically glamorous." She would soon discover that the key lay in one of the DuPont chemical company's newest synthetic fibers: Lycra. The company had spent decades developing Lycra in a quest to design a better girdle, but thanks to Gilda, its triumph would come not from restricting women's bodies but setting them free.

In the 1940s, when DuPont launched its multimillion dollar effort to invent the perfect sturdy-but-stretchy fiber — or spandex, as engineers began to call it, which was an anagram of expands — it had one objective: to revolutionize and then dominate the girdle industry. That's because, at the time, pretty much every woman over the age of 12 was wearing one.

"In the period when Dupont was casting around for new synthetic fiber opportunities, it was taken for granted that a woman should not appear in public, and hardly in private, unless she was wearing a girdle," writes the anthropologist Kaori O'Connor, who in the early 21st century gained rare access to the company's archives and in 2011 published Lycra, an investigation into the birth of the fiber. Girdles were a "hallmark of respectability" and a prerequisite for looking good in clothes.

But the experience of wearing a girdle was hellish. This was partly due to the fabric, which was made from a stiff rubber-covered thread that makes today's Spanx — even more extreme waist trainers — seem forgiving by comparison.

When DuPont surveyed American women about their dream innovations, they consistently asked for more comfortable girdles, and the company saw the potential for massive earnings. Eventually, in the early 1960s, a DuPont chemist named Joe Shivers revealed a fiber that was lighter than rubberized thread but had much more restraining power. The company named it Lycra. Cut to: stretchy girdles aplenty.

At first Lycra girdles were a hit, and demand outran supply. Then, a curious thing happened. Despite the fact that the first massive wave of baby boomers were becoming teenagers — the age when most women began to purchase figure shapers — girdle sales started to fall. DuPont and the rest of corporate America had assumed that the young baby boomer women would shop and dress like their mothers. Instead, as the 1960s unfurled, they were faced with what legendary Vogue editor Diana Vreeland dubbed the "youthquake" — with miniskirts and Mary Quant and a full-on fashion rebellion.

Throughout the decade, DuPont poured resources into trying to keep women in girdles. They even launched an item called a "form-persuasive garment" aimed specifically at the teen market, in case it was the word girdle to which teens were averse. (It wasn't. And adults felt the same.) Despite popular legend, few women in the late '60s and early '70s burned their bras, but most actually trashed their girdles. When the president of the undergarment giant Playtex called up his marketing firm in a panic to report that his own wife had thrown away her girdles, according to the 1997 book Rocking the Ages, the end seemed nigh.

"'Getting rid of the girdle' emerged as a significant cultural moment, in every sense a defining act of 'emancipation,'" writes O'Connor. "Its abandonment was political action on the personal level, an act of liberation through stuff."

By 1975, girdle sales were half of what they had been a decade earlier. With American women now moving about happily unbound, warehouses filled with unwanted girdle fabric, rolls upon rolls dyed a rainbow of vibrant colors. Gradually, small professional dancewear manufacturers and seamstresses began to snatch it up to make garments that, they discovered, "hugged the body and moved with it in a way that had never been possible before."

But it was Gilda Marx who would bring these new leotards to the masses.

Gilda teamed up with a manufacturer who until then had specialized in car seat upholstery; her home was converted into a leotard laboratory where she experimented with different Lycra blends until she landed on her holy grail.

In 1975, she introduced the Flexatard, a nylon-Lycra blend leotard with all the support of a girdle and none of the cultural baggage. Flexatards came in long-sleeved, cap-sleeve, and spaghetti strap versions. And they came in dark, chic colors (red and burgundy and navy) and later, yellow and peach and green and raspberry.

She opened a small boutique in her penthouse exercise studio and began selling Flexatards to students who served as a kind of instant focus group for her products. "One day I looked at the back of my class and saw Bette Midler with arms, legs, and everything flying," she wrote in Body by Gilda. "She was having a wonderful time" — and wearing a Flexatard. "After the class a panting Divine Miss M bounced up to me and said, 'I absolutely adored this workout and this leotard is great. It is the first leotard that was ever able to support my chest.' To a leotard designer, that was the ultimate challenge and the ultimate compliment."

Gilda incorporated as Flexatard, Inc., and before long, women in aerobics classes across the country would be wearing her garments. Dancewear giants Capezio and Danskin got in on the game, too, and began making their own colorful Lycra-blend attire for aerobic dancers. In Britain, a former model named Debbie Moore was building her own dance empire at the Pineapple Dance studio. She built on Gilda's designs, working with DuPont to blend cotton with Lycra and release an even more comfortable line of leotards and dancewear. Her footless tights became predecessors to today's leggings.

When anthropologist Kaori O'Connor interviewed women about their memories of slipping into Lycra leotards and leggings for the first time, they told her it felt exhilarating. The fabric bonded women exercisers, they said, by serving as a kind of collective aerobics uniform that "seemed to free the body and hold it, cover it and yet expose it."

Lycra became the second skin for a new life in which self-confidence would be rooted in women and their bodies, not in rules, dress codes, wearing clothes that were ‘appropriate’ for age or social status.

By the early '80s, Lycra leotards and leggings would burst out of the studio and onto the street, as Gilda and other designers introduced tops, skirts, and shorts that allowed women to come and go from aerobics class without having to change. Dancewear also became popular among women who liked their fresh, edgy "fashion look." (Think: Jennifer Beals in Flashdance and early Madonna.) In 1984 alone, American women purchased 21 million leotards. An aesthetic that still feels like textbook '80s was born.

This represented a paradigm shift in the way women viewed their physicality. "Lycra became the second skin for a new life in which self-confidence would be rooted in women and their bodies, not in rules, dress codes, wearing clothes that were 'appropriate' for age or social status, and especially not in wearing girdles," writes O'Connor. "What had been the ultimate fiber of control now became the defining fiber of freedom."

In the years that followed, middle-and upper-class Americans' wardrobes became increasingly dominated by activewear, as signaling that one cared about working out was as important as actually working out (a trend that lives on, especially in fashion). "Now all the world was a gym and our closets were fast becoming lockers," wrote the journalist Blair Sabol in her 1986 book The Body of America. "In fact, jock couture was probably the first time American designers became an honest fashion force. We had the handle on sweat and lifestyle, while Europe continued to runway sleek and fantasy."

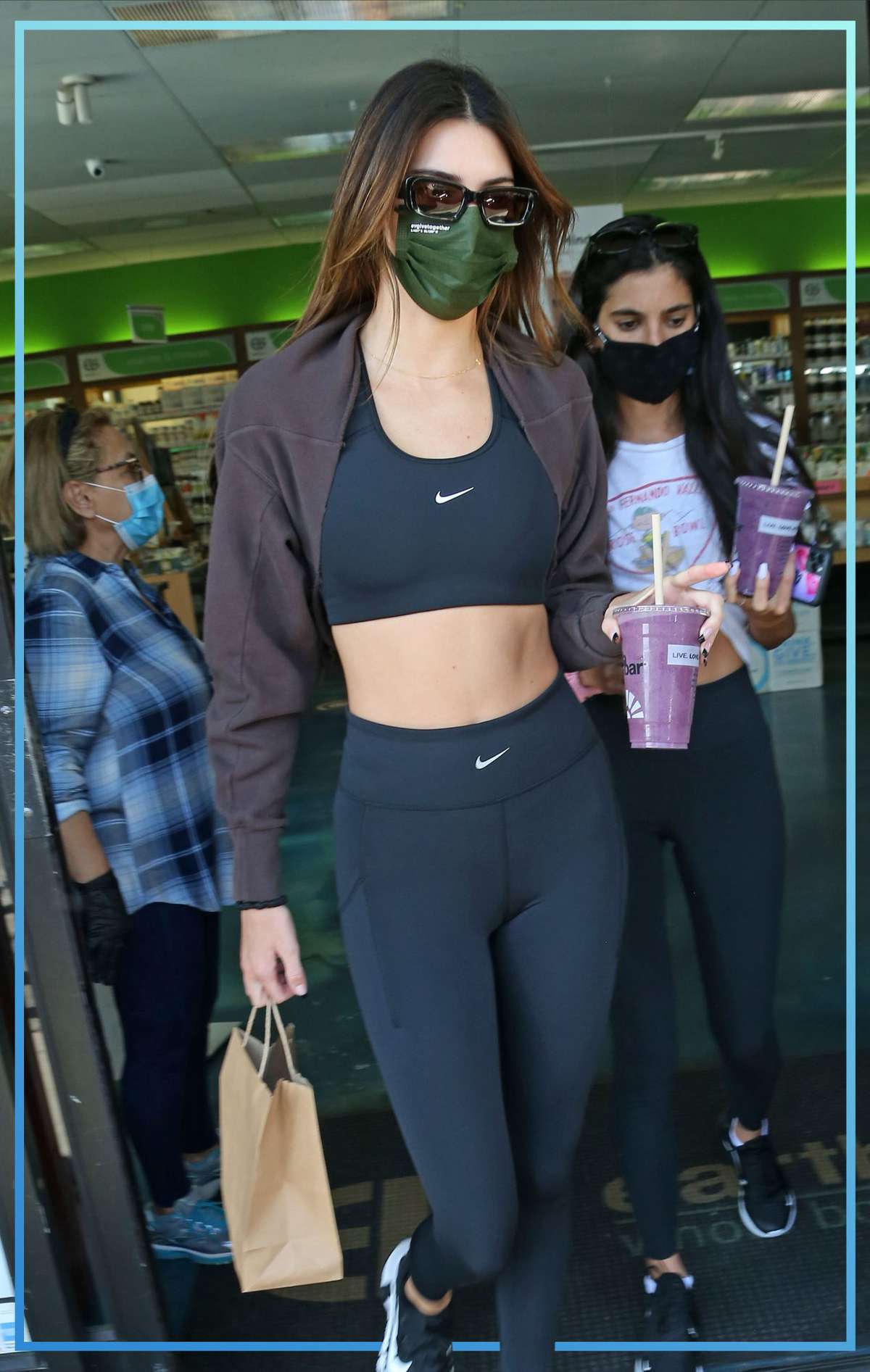

By the 1990s, workout leotards and tights were increasingly replaced by Lycra sports bra tops and bike shorts, as girls whose moms had worn Gilda Marx's Flexatards came of age and put their own spin on sweat couture. Buns of Steel frontwoman Tamilee Webb appeared in the iconic early '90s home workout video series in a sports bra and bikini bottoms, all the better to show off her aspirational hard body; in the 1995 movie Clueless, Cher (Alicia Silverstone) goads Tai (Brittany Murphy) to sculpt her own body in Tamilee's image while both women don bike short silhouettes. Princess Diana helped to make the bike short fashionable as everyday wear, often pairing graphic tees and sweatshirts with colorful Lycra bottoms.

As yoga exploded across America in the second half of that decade, it birthed yet another booming Lycra apparel industry (much to the dismay of yogis who taught their disciples to seek spiritual rather than material wealth). The supermodel yogi Christy Turlington launched her own line of proto-athleisure in the mid-'90s, and Lululemon was founded in 1998; its iconic fabric, luon, is a blend of nylon and Lycra. Madonna, once again, helped to take gym fashion from the studio to the street when she became a poster woman for yoga with her 1998 album Ray of Light, an homage to her practice. Yoga pants were here to stay.

Most recently, the pandemic has ushered in an era of unprecedented sartorial comfort, as women, confined to their homes, now swaddle themselves in whatever stretchy, forgiving fabrics bring them pleasure. Contemporary athleisure — or "athlivesure"as InStyle recently dubbed it — is less its own distinct look than an amalgam of the past few decades's styles; we're wearing sports bras and bodysuits and bike shorts and yoga pants in whatever way feels good. In something of a full-circle moment, today's trending workout wear is also hewing back toward the look of corsetry. It's important to note, though, that this is a result of a new form of sexy dressing kicked off by Bridgerton more than a prescriptive requirement to be cinched. (Kardashian-beloved waist trainers are somewhere between the two; they promise shape-related "results," but they don't hold nearly the cultural grip on women's bodies as their forerunners did.)

The last few years have, after all, seen major workout wear brands, from Athleta to Lululemon, begin to feature models in a wider range of sizes, as our cultural understanding of what a "fit body" looks like is evolving and we are reconsidering our aversion to "dimples" and "rolls." While truly size-inclusive workout wear is still limited — with a few shining exceptions — we appear to be inching closer to a place where all women can have access to the kind of physical liberation and pride that straight-sized women have been experiencing since Gilda led them away from girdles into leotards' light in the 1970s. Now we just call yoga pants "flare leggings," and we wear them wherever we want.

Some, still argue that Lycra clothing — especially of the compressing, control-top variety — is merely a girdle by a different name. But personally? I'd much rather slip into spandex designed to help me dance, run, sweat, and generally move with ease than a figure shaper meant to cinch my body into one socially acceptable form. Fashion that expands often allows women to do the same.

Danielle Friedman is the author of the new book Let's Get Physical: How Women Discovered Exercise and Reshaped the World, a cultural history of women's fitness.

Source: Read Full Article