Tim Robinson loves spicy food.

This minor fact is one of the major things I learned at my very awkward dinner interview with Robinson and Zach Kanin, creators of the cult Netflix comedy series “I Think You Should Leave.” Robinson ordered drunken spaghetti with tofu — spicy — and, almost immediately, the spaghetti started to make his voice hoarse. He insisted, however, that this had nothing to do with the spice — in fact, he said, his food wasn’t spicy enough. I asked our server if she could go spicier. She brought out a whole dish of special chiles. Robinson spooned them enthusiastically over his noodles.

As I watched Robinson eat big red bites of his meal, I imagined a comedy sketch in which a man (played by Tim Robinson) gets himself out of an awkward dinner with a journalist (played by someone who looks exactly like me) by loading his food with increasingly hot peppers until he begins to lose control of his body. The sketch would end with him being wheeled away on a stretcher, on the brink of death — twitching, covered in filth, weeping — but also smiling.

That would actually be a fairly tame premise for “I Think You Should Leave.” The show specializes in ratcheting mildly tricky social situations up to unbearable levels of cringe. It drives the good old vehicles of sketch comedy (corporate meetings, commercial parodies, game-show spoofs) into newly excruciating territory. If that sounds unpleasant, it often is — but it is also hilarious and bold and surprisingly poetic and addictive. Most of the sketches are short, and therefore easy to binge, which means that if they happen to vibrate on your comedy wavelength you will find yourself bingeing and rebingeing them until your favorite lines get stuck in your head for days, like music, and you end up talking almost exclusively in Tim Robinson references (“It’s interesting, the ghosts”) until your family asks if you might please stop soon.

Over its first two seasons, “I.T.Y.S.L.” inspired a giddy and devoted following that spread memes and merch across the internet. Even if you’ve never seen an episode, you have probably encountered stray images from the show in the daily slush of content we all drink from our screens. You may have seen Robinson on Instagram, grinning in a hot-dog costume, standing next to a hot-dog-shaped car that has crashed into a storefront, saying, “We’re tryin’ to find the guy who did this and give him a spanking.” Or on TikTok, squinting his eyes and shouting, in a strange strangled voice that sounds almost too agitated to get out of his throat: “You SURE about that? YOU SURE ABOUT THAT???”

At the Thai restaurant, over dinner, Robinson was not shouting. In person, he is shy, mild, polite, sincere. He’s from Michigan, and he has a salt-of-the-earth Midwestern vibe. He speaks reverently about his family. He loves being a dad, he told me, and his kids are great kids (he has two, 12 and 13), and his wife, who was once his high school sweetheart, is an electrical engineer for Chrysler. “She’s smart,” he said, with feeling.

It was strange to watch this man, whose face I had studied through so many violent comic contortions, in a subdued real-life setting. Robinson’s face is both anonymous and one of a kind. He has a big flaring dolphin fin of a nose; small, deep-set eyes that sit in little pools of shade; a warm, gaptoothed smile. His resting expression is bland, sweet, harmless — he looks, most of the time, like an absolutely standard middle-aged white guy who might be sitting next to you at an airport or a marketing conference. Someone you would feel perfectly comfortable asking to watch your stuff if you had to get up to go to the bathroom.

But when Robinson activates that face, all kinds of amazing things happen. Tiny microexpressions ripple across it at high speed. He seems to have extra muscles in his forehead, because he can knit the space between his eyebrows into lumpy little mountain ranges of confusion, skepticism or disappointment. His quiet mouth gets very wide and loud. And his voice does things I’ve never heard a human voice do. It puffs up, squishes down, turns itself inside out. He can chew on his voice like a cow chews its cud.

Robinson has mentioned in interviews that he has anxiety. I asked him if he still struggles with it.

“Yeah,” he said, solemnly. “It gets worse. It gets worse, the older I get.”

I had been warned that Robinson is deeply uncomfortable doing media. He dislikes, especially, being asked to analyze his comedy. That night, he and Kanin were exhausted. It was April, and they were nearing the end of the marathon process of finishing Season 3, basically living in the editing room, watching sketches over and over, trying to cut the material ruthlessly down to its essence. Their deadline was uncomfortably close; a writers’ strike was looming. They had no idea what day of the week it was. Netflix P.R. had very clearly forced them to meet with me against their will. (They agreed, after many weeks of pressure, to an 8 p.m. dinner at a restaurant that closed at 9.) They were friendly, but in the way you might be friendly to a dentist who is about to extract your wisdom teeth.

I tried my favorite icebreaker question: “What is your very first memory?”

Robinson said he couldn’t remember one. Neither could Kanin.

“How many alternate titles did you guys have before you settled on ‘I Think You Should Leave’?” I asked.

“That’s a great question,” Robinson said.

“We had a lot,” Kanin said.

“What were some of them?” I asked.

They couldn’t remember.

That’s how it went the whole time. Our conversation never took off. And the topic we kept returning to, the thing that flowed most naturally, was our small talk about spicy food.

“Hey, that’s something good for the interview,” Robinson said.

“That could be the headline,” Kanin said. “TIM ROBINSON LIKES IT SPICY.”

Robinson spooned more chiles onto his noodles.

“That’s the thing about spice,” he said. “It’s addicting.”

Soon, mercifully, the restaurant closed, and we said goodbye, and they went off to do more late-night editing.

Over the past 20 years, American culture has been gorging itself nearly to death on cringe comedy. “The Office”, “Curb Your Enthusiasm,” “Veep,” “The Rehearsal.” What is this deep hunger? Why, in an era of polarization, widespread humiliation and literal insurrection — in a nation full of so much real-life cringing — would we want to watch people simulating social discomfort? It hurts enough, these days, just to exist.

I think it’s for the same reason, actually, that we enjoy eating spicy food: what scientists call “benign masochism.” In a harsh world, it can be soothing to microdose shots of controlled pain. Comforting, to touch the scary parts of life without putting ourselves in real danger. Humor has always served this function; it allows us to express threatening things in safe ways. Cringe comedy is like social chile powder: a way to feel the burn without getting burned.

And so we take pleasure watching Larry David saunter around instigating petty grievances, testing the boundaries of our social rules like a velociraptor systematically testing the electric fences in “Jurassic Park.” Or Nathan Fielder, with his laptop on its holster, robotically plotting flow charts, conducting experiments to try to determine, once and for all, what is and is not allowed.

Because it’s tricky, being a person in a society. You have your needs, your wants, your whims, your dreams, your appetites, your fantasies, your frustrations. But — unless you are a castaway or a sociopath — you have to square those things with the needs of some larger group. More likely, multiple groups. Which means you must follow the rules. What rules? So many rules! Laws, norms, mores, superstitions, sentence structures, traffic signals — vast, overlapping codes, written and unwritten, silent and spoken, logical and arbitrary, local and global, tiny and huge, ancient and new. Some rules are rigid (stop signs), while others are flexible (yield signs) — and it’s your job to know the difference. Not to mention that the rules are never fixed: With every step you take, with every threshold you cross, the rule-cloud will shift around you. It can change based on the color of your skin, the sound of your voice, your haircut, your accent, your passport. Sometimes even the thoughts you supposedly have in your head.

“I.T.Y.S.L.” is obsessed with rules. Its characters argue, like lawyers, over everything: whether you’re allowed to schedule a meeting during lunch (no), whether celebrity impersonators are allowed to slap party guests (at certain price points, yes), whether you’re allowed to swear during a late-night adults-only ghost tour (it’s complicated).

Robinson understands a nasty little paradox about rules: The more you believe in them — the more conscientious you are — the more time you will spend agonizing, worrying, wondering if you are doing things right.

This obsession makes “I Think You Should Leave” the perfect comedy for our overheated cultural moment. The 21st-century United States is, infamously, a preschool classroom of public argumentation. Our one true national pastime has become litigating the rules, at high volume, in good or neutral or very bad faith. “Norms,” a concept previously confined to psychology textbooks, has become a front-page concern. Donald Trump’s whole political existence seems like some kind of performance-art stunt about rule-breaking. The panics over “cancel culture” and the “woke mob” — these are symptoms of a fragmented society wondering if, in a time of flux, it still meaningfully shares social rules. Every time we wander out into the public square, we risk ending up screaming, or screamed at, red-faced, in tears.

“I Think You Should Leave” makes comedy, relentlessly, out of moments when the social rules break down. When things stick, grind and break.

Almost always, sketches start quietly. The show reproduces, with loving accuracy, our small-talk, our polite jokes — the way groups use humor to defuse social tensions. A woman, holding her friend’s new baby, says to her partner, teasingly: “Maybe we could have another.” To which he responds, with a nervous grin: “Uh, let’s talk about that later.” Men at a poker game trade jokes about their wives. (“Trust me, my wife has nothing to complain about — unless you’re talking about every little thing I’ve ever done!”)

A lot of “I.T.Y.S.L.” sketches seem to start with a little thought experiment: What would happen if someone took this throwaway joke literally and seriously? How would it warp social reality if these anodyne little pleasantries were actually brought center stage — if someone ignored all the rules we are supposed to intuitively understand?

This is the premise of one of the show’s best sketches, a sketch I’ve memorized so deeply I can hardly even see it anymore. A man at a party is allowed to hold a baby, which cries as soon as it nestles into his arms. “It’s not a big deal,” he says, good-naturedly. “I guess he just doesn’t like me.” That’s a classic, lukewarm, tension-defusing witticism, and everyone smiles politely. But Robinson has invented a guy who takes this absolutely seriously, who becomes obsessed with explaining to everyone, at the top of his lungs and at great length, precisely why the baby doesn’t like him — because it knows, somehow, that he “used to be a piece of [expletive].” Gradually, the man hijacks the entire party with obsessive explanations of all the many ways he used to be reprehensible — “slicked-back hair, white bathing suit, sloppy steaks, white couch.” And he insists, over and over, that “people can change.” The reasoning is absurd, and yet he is so sure and persistent and literal that it becomes a kind of social contagion. By the end of the party, everyone has come over to his side — including the baby, who smiles at him.

Robinson is a genius at stepping into these in-between social spaces — chitchat, reassuring smiles — and zeroing in on the tension at the heart of it all. Then he will isolate that tension, extract it and inflate it like a balloon until it fills the whole room, until it fills the whole universe. He is a virtuoso of social discomfort.

Tim Robinson grew up in the suburbs of Detroit. His mother worked for Chrysler. As a kid, he disliked school. He had no idea what he was going to do with his life. But then he went to a show that changed his life: a traveling troupe from Second City, the famous Chicago comedy group. Immediately, Robinson thought: Oh. This is what I want to do. So he did.

The comic actor Sam Richardson, who also grew up in Detroit, told me he first saw Robinson perform in a suburban bowling alley. “I was like: This guy is the funniest dude in the world,” he said. “His cadence is so specifically his own. You can’t teach it. It’s incredibly human. It’s human beyond human.” Robinson quickly became a star in the local scene — Richardson said he was, hands down, the best improv comic he’d ever seen. “Hands down,” he repeated. “Like, all hands go down. I’ve never seen Tim flounder in a scene. We all flounder. But he could always just find the ball and dunk it. It was incredible.”

Robinson’s talent propelled him out of Detroit to Chicago, after he joined Second City — and then eventually to New York, where he signed on as a cast member of “Saturday Night Live.” There is a clip that sometimes circulates on social media of Robinson, in a bit part on a forgettable “S.N.L.” sketch, making the host, Kevin Hart, break out laughing over and over. Although none of Robinson’s lines are particularly funny, he has an instant presence and charisma. He doesn’t even have to say anything; he just embodies some species of funniness that no one else can touch. It would have been easy to imagine him blooming into his generation’s Will Ferrell or Kristen Wiig.

But it was not to be. Robinson’s sensibility was too specific and weird. His anxiety was crippling. His sketches kept being cut.

“Tim would call me every Sunday morning and just be so broken down,” Richardson told me. “He’d say things like, ‘Maybe I’m not funny.’ He was grossly unhappy.” Richardson went to an “S.N.L.” taping once, during the holidays, and he remembers Robinson standing backstage in a Santa costume, beside himself with excitement because one of his sketches was scheduled to get on the air. Then, at the last second, it was cut. Robinson was crushed.

Robinson was dropped from the “S.N.L.” cast after just one season. But he didn’t leave. Instead, he joined the writing staff. And this is when everything started to change. He found a comedy-writing soul mate in Zach Kanin, another staff writer, who was his polar opposite in terms of background (well-connected East Coast family, Harvard Lampoon, New Yorker cartoonist) but had exactly the same sense of humor. Robinson and Kanin shared an office and became a power duo. Although plenty of their sketches never made it to the air, they were always a hit at table reads. They were the cool guys, the artists. They just needed their own vehicle.

It took a while to happen. Netflix let them make an episode of the anthology sketch show “The Characters” — and it was wild and foul and brilliant, the standout episode of the season. For Comedy Central, Kanin and Robinson made a sweet, kooky sitcom called “Detroiters,” co-starring Sam Richardson. That gained a cult following but was canceled after two seasons.

This all led, eventually, to “I Think You Should Leave”: the full, shocking, unapologetic flowering of their weirdo comic vision.

“I.T.Y.S.L.” creates, with shocking efficiency, a whole comic universe. There are so many sketches I’d like to describe. The one in which a prank-show host has an existential breakdown at the mall because his costume is too heavy. (He is pretending to be “Karl Havoc,” a huge guy in a wacky vest who messes with people in the food court — but he ends up just standing there, frozen, hulking and dead-eyed, muttering to his producer: “I don’t even want to be around anymore.”). There’s the sketch in which a man at a restaurant won’t admit he’s choking because he doesn’t want to look dumb in front of the celebrity who is sitting at his table. But the brilliance of these sketches never comes from the premise alone. Instead it’s in the rhythms, in the gymnastics of Robinson’s face and — especially — in the strange poetic writing. The way language glops out of everyone’s mouth like soft-serve ice cream. “I can’t know how to hear any more about tables!” a driver’s ed teacher yells at his students, after they won’t stop peppering him with questions about the bizarre centrality of tables in his instructional videos. “And now you’re in more in trouble than me unfortunately,” a man says to a co-worker who’s lost his temper.

“It always feels like improv, when you’re watching the show, but it is not,” Akiva Schaffer, one of the show’s directors, told me. Robinson and Kanin are meticulous about their scripts — everything that feels slightly “off” is written exactly that way. That odd driver’s-ed-sketch sentence, Kanin told me, came from something his young daughter said. In fact, many of the show’s men, when they are agitated, speak like children: their words forced out by the pressure of need, right on the edge of coherence. Robinson shared a memory from his childhood. Once, when he was a kid, his family moved to a new house, and he and his brothers went out to play in the backyard. A boy next door stared at them, so they stared back — until, finally, agitated, the boy yelled: “Stop keep looking at me!”

Robinson’s comedy is, as my wife has put it, “very male.” (She is, to be clear, a fan.) There’s a lot of yelling and nasty language and juvenile behavior. There are colorful synonyms for poop (“mud pie,” “absolute paint job”). When a man’s ego is threatened, the whole universe seems to hang in the balance.

But it would be a mistake to confuse Robinson’s comedy with the usual “very male” comedy: the archetypal bad boy, swinging his id around, railing against P.C. culture and his nagging wife, preaching that the rules are stupid, that society is a scam and a cage, that we should follow our desires and never negotiate and certainly never apologize.

Robinson’s comedy is doing something much more interesting. This is comedy of the superego. It understands that every moment of human life requires a negotiation with rules — and that this is hard, and stressful, and there are so many ways it can go wrong. But the negotiation is also vital. The rules, after all, are holding some pretty destructive forces back.

One of my favorite things about “I.T.Y.S.L.” is all the crying. Robinson’s characters cry while driving and at parties and in the middle of work meetings — after, say, a man chokes on a hot dog he’s been secretly eating out of his sleeve, or after the boss makes him take off his ridiculous hat. One man tries to defuse a tense situation by doing a whole zany “Blues Brothers”-style dance — but it backfires, making everything worse, and so he pulls off his sunglasses to reveal a puffy wet red face.

When a Tim Robinson character cries, it is a result of an epic struggle for selfhood — a Greco-Roman wrestling match between the man’s public persona (confident, respected, “normal”) and the private, vulnerable self that he alone secretly knows. Those two selves collide, like plates on a fault line, and what gushes out are all the molten emotions the man has spent his whole life stuffing down. His terror of vulnerability leads to an eruption of vulnerability. It is hilarious and troubling but also touching. You want to shun the man and yet you also want to hug him — until you want to shun him again. (Almost inevitably, while the tears are still flowing, Robinson’s character will double and triple down on whatever got him in trouble in the first place.)

“These guys are really having a hard time,” Schaffer told me. He said Robinson and Kanin’s extremely meticulous scripts originally contained zero crying, but it arose naturally during filming. “We would do three takes and I’d be like: ‘Oh, this guy should start holding back tears,’” Schaffer said. Then, sketch after sketch, they’d realize: “Wait a minute, this guy seems like he might be getting teary, too. We started joking: Should every character be crying by the end?”

Robinson’s tears come out in a variety of ways. Sometimes his eyes just get big and wet — as in one sketch, when a man gets caught after secretly complaining to the waiter that his otherwise wonderful date has been eating all the best bites of their “fully loaded nachos.” (“Just say the restaurant has a rule,” he pleads with the waiter. “One person can’t just eat all the fully loaded ones.”) Sometimes a single tear comes trickling down his cheek — as when an office worker can’t reciprocate when his co-workers are sharing viral videos. What is clear, in each case, is that the tears are coming from an extremely deep place, like the purest artesian well water. Something is being squeezed out of these men, under tremendous pressure — some kind of sacred male pain-juice.

This is a big part of what sets “I.T.Y.S.L.” apart from other cringe comedy. Despite its loudness and brashness, it is somehow fundamentally touching and vulnerable and sad. Its tenderness keeps it bearable. Robinson’s characters are rarely proud of their antisocial behavior. They want, desperately, to follow the rules. They are searching, as hard as they can, for the elusive balance between self-interest and the interests of the group. They just can’t seem to find it. The pain of that leaks out of their eyes. And then, before long, the screaming begins.

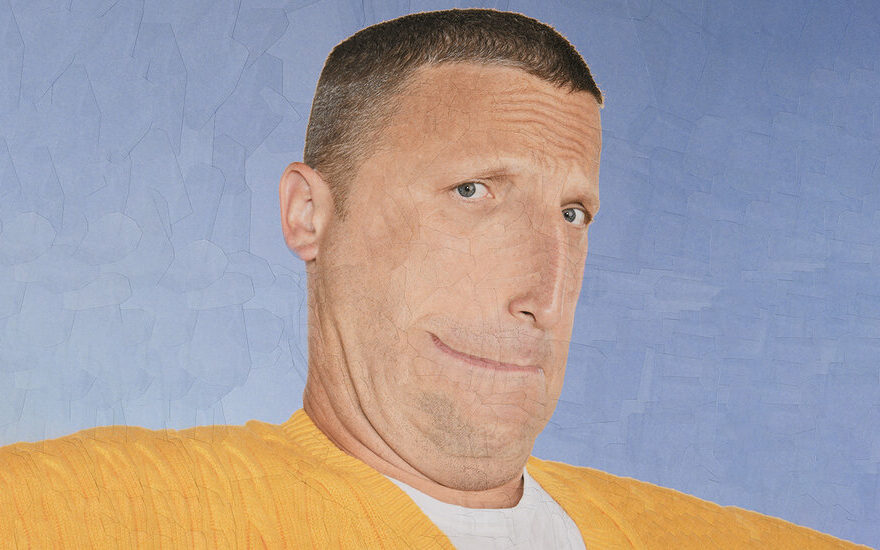

Opening illustration: Source photograph by Atiba Jefferson/Netflix

Sam Anderson is a staff writer for the magazine. He has written about rhinos, pencils, poets, water parks, basketball, weight loss and the new Studio Ghibli theme park in Japan. Lola Dupre is a collage artist and an illustrator currently based near Glasgow, Scotland. Working with paper and scissors, she references the Dada art movement and is influenced by modern digital-image manipulations.

Source: Read Full Article