Listen to This Article

To hear more audio stories from publications like The New York Times, download Audm for iPhone or Android.

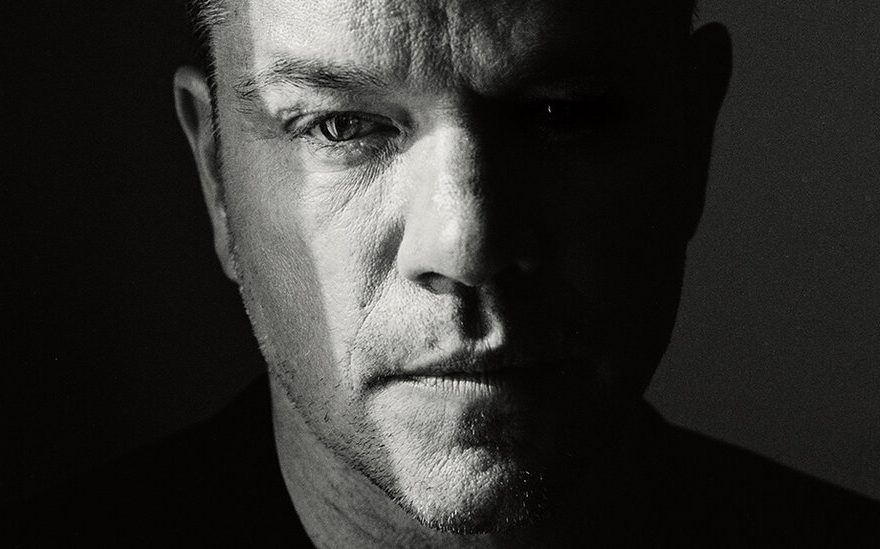

“There’s a great lesson here for an actor,’ Matt Damon said, a dusting of gray in his short hair and thin goatee, fine age lines around his pale blue eyes. It was early May, and he was speaking via Zoom from a sparsely appointed, sun-splashed room in a rented house in Sydney, Australia, telling a story about working with Jack Nicholson on Martin Scorsese’s 2006 dirty-cops-and-criminals epic, “The Departed.” “The scene was an eighth of a page,” Damon said, arching his eyebrows devilishly and adopting Jack’s insinuating vocal tones. He was recalling the older actor’s talking about reworking a scene in which his character, the Boston gangster Frank Costello, is supposed to murder a man in a marsh. “Jack looked at that scene” — and, truly, it was almost startling how well Damon captured Nicholson’s disquieting energy — “and he goes: ‘What I did was I made the person being executed a woman. That’s sinister. Costello executes a guy in a marsh? We’ve seen that kind of scene in movies before. That’s not what I did.’”

Damon smiled, showing his big, bright teeth (his physical feature that is most undeniably a star’s), as he described Nicholson’s filigrees becoming increasingly macabre, adding, for example, intimations of necrophilia and then punctuating each with “Now, that’s sinister” to make sure his young co-star caught his drift. “I was like, ‘Yep, it is, it’s pretty awful,”’ Damon said, his voice cracking as he relived his squeamishness. Scorsese wound up cutting almost all of Nicholson’s jazz. But that’s not the lesson. The lesson, Damon explained — dressed on this day, as he was each time we talked over several weeks this spring, in a pale shirt and wearing a tatty string bracelet that one of his daughters had woven for him — “was that Jack started with something we’ve seen plenty of times and kept trying to make it as good and as interesting as it could possibly be.”

Damon has learned that lesson well, though he expresses it in a very different way from Nicholson, who no matter the part always conveys an innate Jackness. Instead, Damon the man can almost disappear. As both a performer and a public figure, he’s a type we’ve seen plenty of times: the regular guy, an All-American, the nice fella who could live next door. But there is also an underrecognized Nicholsonian edge, a darkness, to many of his roles, which perhaps bespeaks the relish with which he offered his impression. All of which is to say that in ways both subtle and not, intentional and un-, he has complicated his relationship with audiences, elaborated and often inverted the idea of Matt Damon.

Over the course of his long tenure near the top of the Hollywood food chain, Damon has often embodied idealized Everymen: the solid, approachable, well-meaning, scrappy characters he has played with seeming simplicity and emotional economy in a long line of very successful movies. There’s the stolid rugby captain Francois Pienaar in “Invictus” (2009); the keeping-it-together dad in the 2011 pandemic procedural “Contagion”; the good ol’ boy auto racing impresario Carroll Shelby, up against them fancy Italians, in “Ford v Ferrari” (2019). Think, too, of his Mark Watney from “The Martian” (2015), an astronaut not about to let being marooned on Mars dampen his geeky enthusiasm for solving lifesaving science problems. Even amid the glamorous milieu of the “Ocean’s” series of heist films, Damon’s pickpocket Linus Caldwell is eager for the approval of George Clooney and Brad Pitt’s suave superthieves, which means he’s more like you or me than he is like them.

Good-Guy Matt Damon

Yet despite being a hugely famous, sympathetic and very bankable American movie star, Damon has always felt distant, hasn’t he? Which is odd, because he has never floated away into the realm of remote screen deity like his contemporaries Leonardo DiCaprio or Brad Pitt or George Clooney — he’s too solidly earthy for that. Nor has insisted on the mysteries of his being in the manner of Tom Cruise. Instead there’s a cipherlike aspect to Damon, a deeper impenetrability to who he is and what he does that even now, after a quarter-century of watching him, has become so entrenched that we take both it and him for granted.

“Fifteen years ago,” said Damon, who nods as he tells his stories, as if encouraging you to follow along, “I was doing press for ‘The Good Shepherd’” — in which he played a dubiously ethical 1950s C.I.A. man, one of many roles that use his four-square good looks and trustworthy air as a feint — “and I went on Larry King’s show with Robert De Niro and Angelina Jolie. He looked our names up on the internet and read out the words that people associated with us. Bob’s was ‘intense.’ Angie was ‘sexy.’ I was ‘nice.’” Then Damon said, jokingly, “I remember being mildly offended.”

When Damon and I spoke, it was night for me in Brooklyn, the borough where he and his family normally live, and morning for him in (at the time) relatively Covid-free Sydney. That’s where he and his wife, Luciana Damon, and their three daughters — a fourth, hers from a previous relationship, is a student at the New School and stayed back home in New York — decamped while he filmed a small part in the director Taika Waititi’s next “Thor” movie. (The family traveled to Australia after Damon wrapped five months of shooting in France and Ireland for “The Last Duel,” directed by Ridley Scott, due out this fall, in which he plays a vengeful 14th-century French knight, Jean de Carrouges, who accuses a squire of raping his wife.) Damon is an amiable, if cautious, interviewee, and to a degree that’s almost disorienting, his vibe is deeply normal. Talking to him was like making conversation with a former classmate or colleague whom maybe you didn’t know all that well but of whom you always thought fondly.

But you only have to look a bit closer at Damon’s career, at the notion of Matt Damon, Movie Star we have in our heads, to see that nice might be an ingenious sleight-of-hand, an illusion of sorts. Because that darkness is there. Damon doesn’t just play nice guys. Far from it. There’s Jason Bourne, whom he has played in four hit films and who is a miserable, self-loathing killing machine; the sociopathic social climber Tom Ripley in Anthony Minghella’s “The Talented Mr. Ripley”; the crooked Colin Sullivan in “The Departed.” Or the prep-school anti-Semite in “School Ties,” an early hint at the lurking appeal of Bad Matt. Damon’s most deftly portrayed cretin may be Mark Whitacre, the self-dealing, weaselly-mustached corporate whistle-blower in Steven Soderbergh’s “The Informant!” His most unexpected heel turn: a cameo as a cowardly astronaut (Mark Watney turned inside out) in Christopher Nolan’s “Interstellar.” “He has a willingness to rip apart his boyish, all-American exterior,” says Soderbergh, who has directed Damon in nine films. “He’s self-aware enough, and secure enough, to riff on that.” Whether another actor could have similar riffing opportunities anymore is doubtful. Over the course of his career, Damon has seen the films like the ones that sustained him — that is, the $20-million-to-$70 million drama, what he calls his “bread and butter” — mostly disappear. “You need those roles to develop as an actor and build your career, and those are gone,” Damon said, nodding. “Courtroom dramas, all that stuff, they can’t get made.” Those sorts of movies have been replaced by more easily exportable, higher-budget but paradoxically lower-risk ones. “You’re looking for a home run that can play in all these different territories to all these different ages,” Damon said. “You want the most accessible thing you can make, in terms of language and culture. And what is that? A superhero movie.”

The big-time movie business’s paradigm may have shifted, but Damon’s choices remain mostly to do with keeping him — and us — engaged. A case in point is the new dramatic thriller “Stillwater,” directed by Tom McCarthy, in which Damon plays an Oklahoma roughneck and former addict named Bill Baker, a man whose heart is in the right place but who sets everything else askew. In the film, Baker’s daughter, played by Abigail Breslin, is serving time in a Marseille prison for the murder of her French-Arabic girlfriend. She claims she’s innocent. Baker travels to the Mediterranean port city to visit her and gets a tip about another suspect. Very loosely inspired by the sordid Amanda Knox saga, “Stillwater” follows Baker as he tries, in his noble but socially incurious and ultimately damaging way, to navigate the foreign city’s legal and social systems. (You would not be foolish to read all this as a metaphor for American behavior writ large.) It’s a film, and a performance, built on a classic Damon subterfuge. In all his down-home, grace-before-dinner ordinariness, Baker is someone to pull for. Then he fouls things up — badly, unethically — and because it’s Matt Damon, you don’t entirely hold it against him.

“Whatever those wholesome associations are that people say I have,” Damon said, relentlessly self-deprecating if not quite straight-up resistant to parsing his own appeal or persona, “having them allowed me a chance to work with clever directors who want to subvert that.” He’s a pleasingly inoffensive, nonthreateningly masculine, apple-pie type, but like so many all-American commodities, there’s more lurking in that designation.

Bad-Guy Matt Damon

Damon has long benefited from a public-facing opacity. This goes back to “Good Will Hunting,” which established Damon as someone to root for after he and Affleck came from somewhere just north of nowhere to write and star in the picture together. Who wasn’t charmed by their Southie characters’ lived-in camaraderie? The ease with which they needled and supported each other? The duo won an Academy Award for best original screenplay and strolled onstage to accept the award with pure enthusiasm, utterly free of jadedness. Didn’t they seem like such nice boys? For one of them, that stuck. Damon, in the years immediately after, managed to freeze his persona in that moment of, well, good will. He had a couple of high-profile relationships (Minnie Driver, Winona Ryder) and then vanished from the tabloids, which he talks about as a career-maintenance move. “If people can see 16 pictures of you drinking coffee or walking your dog,” Damon said, “I think it dilutes the desire to see you in a movie.” Some of this insight has most likely been arrived at through his proximity to Affleck, who has not been able to avoid tabloid attention so effectively: We know about his relationships, his addiction problems, his preference for iced beverages from Dunkin’, his propensity to look sad when snapped by a long-lens camera.

Damon has seen how this extracurricular attention affected Affleck’s career. When Affleck and Jennifer Lopez, Bennifer 1.0., were first throwing off sparks in 2003 — a year that included the couple’s notorious flop, “Gigli” — Damon’s and Affleck’s longtime agent, Patrick Whitesell, made a phone call to the editor of a celebrity magazine then regularly featuring Affleck on the cover. He asked the editor to go easy. “Patrick said, ‘You’re ruining this man’s career,’” Damon told me. “The editor’s response was like, Sorry, they’re buying those issues in Ohio and Kansas, so we’re going to keep putting him on the cover.” (Whitesell says the purpose of that call was to express his dissatisfaction with the magazine’s reporting of “gossip, not facts.”) Damon says Affleck confided in him that “I’m in the worst place I can be. I can sell magazines but not movie tickets.” He worked hard to rebalance that equation.

Affleck, who wrote “The Last Duel” with Damon and Nicole Holofcener and also acts in the film, understandably had reservations when I raised this subject with him. “In your asking about it there’s a subtle implication or judgment,” he said, “that I chose to seek out attention, and Matt didn’t. He and I have both assiduously tried to maintain our privacy.” He added, “I’m not a psychiatrist, but I would think that the process of suspending disbelief when watching an actor would be more difficult for an audience if they knew more about the person they’re watching.”

Here’s what we know about Matt Damon: He and his older brother, Kyle, were raised in Cambridge, Mass. by their father, Kent, a stockbroker, and mother, Nancy Carlsson-Paige, an emeritus professor of early-childhood education. The couple divorced when the boys were small children, but the relationship remained amicable. “They really co-parented,” offered Damon, whose posture stiffened slightly when questions crept toward the personal. Damon said his mother knew that he’d be an actor from the time he was a small child. A family legend has it that when his mom accidentally started a fire in their apartment by forgetting to open a fireplace flue, 6-year-old Matt’s response was to don a makeshift fireman’s costume and pretend to put it out. He went to Harvard, planned to major in English, dropped out after landing a part in the 1993 western “Geronimo” and never seriously harbored thoughts about having a different job. “I used to feel bad when friends would talk about their future after college and they didn’t know what they were going to do,” Damon said. “I always knew.”

Damon and his wife met in Miami, where she was working as a bartender and he was filming the Farrelly brothers’ slapstick comedy “Stuck on You,” and have now been married for 16 years. Their four daughters range in age from 10 to 23, and their influence means the online presences of Taylor Swift and Timothée Chalamet have been a source of pleasure to their father, whose own social media presence is basically nonexistent. The family’s home in Brooklyn Heights, according to The New York Post, was the most expensive private residence in the borough at the time of its purchase in 2018. For fun while in Australia, he’d been doing some surfing (“I’m pretty terrible,” he said) and horseback riding. The last nonfiction book he read was “Hate Inc.: Why Today’s Media Makes Us Despise One Another,” by Matt Taibbi. The last novel: “The Searchers,” by Alan Le May, which was made into the classic 1956 western and which he’d been sent by producers mulling a remake. “What else do I do? ” Damon said when I nudged for more. “I don’t know, I sound like a pretty boring guy.”

Call it what you will, boring or shrewd, but Damon sees himself as “in the last of that line of people who want to maintain privacy,” he said. “There’s this new line of people inviting everybody into their daily lives: Hey, I’m at the gym! This is me working out! There’s something tactically brilliant about it in the sense that you’re controlling the narrative, but it’s the exact opposite of how I’ve always thought, which is ‘Move on, nothing to see here,’ and just doing the work.” This idea, that knowing where a movie star buys his coffee undermines the audience’s ability to suspend disbelief — to imagine — is a hoary one, and also one we tend to hear coming from the mouths of older white guys, at least those lucky enough to opt out of feeling the pressure to build an audience without selling too much of themselves. But that doesn’t mean there isn’t anything to it.

‘Brad probably wouldn’t even remember how many of the movies that I’m in that he was offered first.’

Even before he was famous, Damon’s impulse as an actor has always been toward a certain inwardness, an emotional mutability he identified in his idols early on. He remembers, thinking back to the fall of 1987, a discussion he and Affleck had backstage at a rehearsal for their high school production of Friedrich Durrenmatt’s bleak morality play “The Visit.” The two boys, students at Cambridge Rindge and Latin School in Massachusetts, were discussing the type of actors they wanted to be when they grew up. Self-taught film nerds in the habit of renting highbrow movies from the local Blockbuster, they’d recently watched the 1985 film version of “Death of a Salesman,” which had ignited a conversation. The movie starred a 48-year-old Dustin Hoffman as that icon of delusional striving, the 63-year-old Willy Loman, and in Affleck and Damon’s estimation, you could see Hoffman working to make that age gap manifest in his performance — you could see the wheels turning. They wondered: Was it good acting when the acting announced itself? Did they want to be actors who did that, self-reflexive technicians? Was it more preferable to be a chameleon? Damon already knew the answer: He wanted to be like Gene Hackman.

When Damon and Affleck were having this conversation, Hackman was 57, seven years older than Damon is now, the star of such classics as “The French Connection” and “Hoosiers” and the sort of actor who disappears into a character but without making a whole show about it — an anti-magician, downplaying his transformation. “Hackman could sit so deeply in a character,” Damon said, “and be so moving even when he was doing very little.” Damon pointed to Hackman’s work in Francis Ford Coppola’s 1974 paranoid masterpiece “The Conversation.” He noted how in his book “In the Blink of an Eye,” the legendary film editor Walter Murch, who worked on “The Conversation” among other classics, found that whenever he went to make a cut, Hackman was blinking, so attuned was the actor to the narrative rhythms of the film. “He was so locked in,” Damon said of Hackman. It was work, like so much of Damon’s, that elevates a movie and yet, paradoxically, that you might not even notice as great acting.

William Goldman’s old saw about how in Hollywood nobody knows anything could probably now be amended to this: Everyone knows only one thing, and it’s that superhero movies sell. The reorientation of the studios toward those films and other pre-existing intellectual property means the power of actors, even proven stars like Damon, has diminished. It’s the recognizable characters and cinematic universes that can be counted on financially, not the people inhabiting them. Fewer attractive parts adds extra pressure on stars to pick those parts wisely — a big, undervalued aspect of Hollywood acting. In hindsight, when you look over a successful actor’s IMDB page, it’s a list of hits and near misses and duds, but originally, they were all the same: a script. Nothing is preordained. Anyone who has a 25-year career as firmly A-list as Damon is good at picking, at telling not just whether a movie will be good but also whether he can be good in it, and whether it can be good for him. “Sometimes the right choice for an actor isn’t the biggest film, but what is the right choice for that moment in an actor’s career,” says George Clooney, who directed Damon in “The Monuments Men” and “Suburbicon.” “Matt has bounced back and forth between big studio pictures and independent, interesting films. Because he doesn’t keep doing the same thing, audiences don’t get bored of him.”

Nowadays, Damon’s solution to the problem of picking is to go with strong directors — a star’s prerogative and nice work if you can get it. Earlier in his career, he wasn’t in a position to be so choosy, but even then he had opinions. His agent, Whitesell, told me a story about young actors competing for the part of an arrogant hotshot alongside Hackman, Sharon Stone and Russell Crowe in the buzzy 1995 western “The Quick and the Dead.” It was a competition that, according to Whitesell, Damon won, blowing the producers away with his audition. “This was a movie that, on its surface, everybody wanted.” He remembers sitting with Damon, who had his doubts, saying: “Sharon Stone — great actress but a female gunslinger? You’re not going to believe the movie.” So Damon removed himself from consideration for the part, which was ultimately played by Leonardo DiCaprio. His instincts were accurate — the film failed at the box office — but it took a pretty confident 25-year-old to bow out of the running like that. “Probably too cocky for my own good,” Damon said.

Not too long after, “Good Will Hunting” rewarded his self-assurance and made Damon a star. At least that’s how we remember it. Whitesell says it was a different film that paved the way for Damon’s breakthrough. “The real key to ‘Good Will Hunting’ getting made,” he says, “was Matt landing ‘The Rainmaker.’” That film, an adaptation of a John Grisham novel that was directed by Francis Ford Coppola and which premiered a few weeks before “Good Will Hunting” in the fall of 1997, turned Damon into a shiny object that other studios were willing to put money behind. “Around then,” Whitesell says, the Grisham movies “were the triple-A thing for a leading young man to get.” Think Tom Cruise in “The Firm,” Matthew McConaughey in “A Time to Kill” and Chris O’Donnell in “The Chamber.” (Here’s to Chris O’Donnell’s ’90s run.) Damon got his Grisham lawyer, and was on his way.

During his stardom apprenticeship, Damon also made the effort to earn his spurs as a young actor and not merely chase a higher fee. He told me a story about working on “Saving Private Ryan” (1998): “I had to take a projectile,” said Damon, who had a small but pivotal role in the film, “and smack it against an ammo box and throw it. As I did I had to scream, ‘Look out for the panzerschreck.’” He did, only to see the film’s star Tom Hanks “laughing so hard he was crying. I went, ‘What?’ and he goes, ‘Sometimes you have to sell the panzerschreck line.’ Which you do.” He learned another useful lesson from Hanks on the same movie. “All us young actors were sitting there with Tom in between takes,” said Damon, “and he said: ‘You are all one movie away from being the biggest movie star in the world. That’s the good news. The bad news is your mailman is one movie away from being the biggest movie star in the world.’”

Even before his education on the downsides of tabloid attention, Damon witnessed other problems that come with Hollywood success. Before “Good Will Hunting,” he and Affleck were sent on a meeting with Hugh Grant, then at his rom-com apex, to see if they could all gin up a project. “He had these ideas,” Damon said of Grant, “and he was explaining them like, ‘Then smoothie Hugh comes in and saves the day.’ He kept referring to himself as smoothie Hugh, like he was completely over it. That system was making him be this thing — and he was great at it, and he has shown he’s more — but that wasn’t all he was.” Damon left that meeting thinking, I don’t ever want to be in that position, where I’m in a box and can’t get out of it. (Asked for comment, Grant said: “They still owe me a screenplay. I’ve been waiting 25 years for it.”)

By 2002 Damon had found Jason Bourne, a character whose films, made over the next 14 years, functioned as a superhero movie should: a sure thing. “With the Bourne movies,” he said, “it was great to have them off in the middle distance, almost like an inoculation. I knew that with them I’d have a movie that as long as we executed it properly, it should work. That frees you up to do all kinds of other stuff. I’d take a supporting role in this one and I’d take another role in that other one and not worry about each of them too much strategically.”

But even at Damon’s Hollywood-mainstay level, the movie-star business is tenuous. A scant few years ago, “Suburbicon” and “Downsizing” fizzled back to back, and the historical fantasy “The Great Wall,” which sure looked like a play for Chinese box office (Damon said he made it, in part, because he admired its director, Zhang Yimou), earned money but was, frankly, a stinkeroo. Damon worried that his career “was in real peril.” He wondered about his place on the List, that intangible, unstable ranking that every star and studio mogul keeps in their head of actors worth the gamble of hanging a movie on. “No one can tell you exactly who’s on the List,” Damon said. “It’s constantly changing month to month, and nobody has ever seen it. But you want to be on it.” He felt more secure when “Ford v Ferrari” scored. If “that hadn’t worked,” he said, “it would have been a big problem for me.”

Damon said that even among the films he does choose to star in, he rarely has first dibs. “Most scripts I get,” he said, “have the fingerprints of another actor on them. Brad probably wouldn’t even remember how many of the movies that I’m in that he was offered first, including ‘The Departed.’” Tom Cruise, too. “I’m sure he’s been offered everything before me. Definitely Leo as well. But as long as I can hang on that list, I might get a crack, which is all you can hope for.”

The roughest patches in Damon’s career, as a public figure anyway, have been due to offscreen rather than on-screen missteps. These were occasions when Damon seemed unaware of larger cultural advances, and as such gave reason to wonder if anything unsavory might be beneath that affable exterior. The first occurred during the 2015 season of “Project Greenlight,” an HBO reality show about first-time filmmakers that Damon and Affleck co-produced and appeared in as mentors to the young talent. In one episode, a producer Effie Brown, a Black woman, raised a question about the show’s lack of diversity. In response, Damon appeared to lecture her on the right way to achieve it — that is, the semblance of it — while also downplaying the importance of behind-the-scenes diversity at all. “When we’re talking about diversity,” he told her, “you do it in the casting of the film, not in the casting of the show.” The comments led to an online backlash, including the Twitter hashtag #damonsplaining, a variation on “whitesplaining,” which Urban Dictionary defined at the time as “the paternalistic lecture given by whites toward a person of color defining what should and shouldn’t be considered racist, while obliviously exhibiting their own racism.”

Then in 2017, at the height of the #MeToo movement’s momentum, Damon, in response to an interview question, said that allegations of inappropriate sexual behavior needed to be seen as existing on a “spectrum.” In these instances, both of which he apologized for publicly, Damon came off as emotionally ignorant, a rich white guy unaware of his own blinkered view. “I was and am tone-deaf,” he told me, no longer nodding but shaking his head contritely. “Like everybody, I’m a prisoner of my subjective experience and that leads to having blind spots. Me more than most given the experience that I’ve had as a white male American movie star. It’s a very rarefied air. I don’t even know where my blind spots begin and end. So, yes, I was and am tone-deaf. I do try my best not to be.”

Like so many in Hollywood, Damon has also had cause to reconsider his previous professional relationships with the producer Scott Rudin, who worked with Damon on “True Grit” and “Margaret” and whose bullying behavior recently came under scrutiny, as well as Harvey Weinstein, who engineered the Oscar campaign for “Good Will Hunting” and in doing so helped make Damon’s and Affleck’s careers. “These are legendarily badly behaved people, and I’d never really seen it,” Damon said. “I’ve had positive working experiences. But it’s sad when people have abused their power and gotten away with it just because they were successful.”

Looking back on this misjudgment, Damon said that the best piece of advice he got at the time came from an old Cambridge friend who told him to focus on listening to the criticisms rather than responding. “It was wise,” said Damon. “I did listen, and once I got out of my defensive crouch. … ” He paused. “I really started to understand what it was I said that people took exception with.”

‘I don’t even know where my blind spots begin and end.’

Presumably as a result of those aforementioned messes and subsequent public scolding, Damon says the prospect of talking about his life or work outside what we see onscreen causes him “a little terror.” It would be terrifying if you were he. Not only has Damon felt the sting of a public screw-up, he also has that determination to keep his private life private. The counterweight to his anxiety, though, is our shared history. Matt Damon is an actor who has often played crooks and killers, and yet all that lingers are those big, bright teeth. We don’t really want to begrudge Matt Damon. We just want to like him.

And yet, Damon is the movie-star epitome of the nice white American male at a time when the trust in, and appetite for, what that kind of figure represents is increasingly suspect. There’s a reason there is no obvious next Matt Damon — and it doesn’t just have to do with the disappearance of the $20-million-to-$70-million movies he came up in. The Matt Damon type is one that no longer has automatic home-field advantage in quite so many people’s hearts. About this idea, the film historian David Thomson says: “We have seen through — at last — the personality archetypes that Hollywood offered us for years. Many of which depend upon the reliability of a superior white character. We just do not believe in those people in the same way anymore.”

Damon says he hasn’t given much thought to such possible shifts, saying only, “It makes sense that as the culture changes, leading men will change.” The audience, he said, “will decide who it wants to see.” Or, more accurate, what it wants to see in those leading men. You can look at the roster of those younger than Damon and see plenty of likable white guys, but they’ve all taken different tracks than he has. To name a few: John Krasinski has made a show, “Some Good News,” rooted in the idea of his wholesome emotional benevolence and since becoming a star has mostly forsaken roles that might disrupt his image. The Chrises — Pine and Evans — have public personas based largely on displaying self-awareness of their type in an attempt to hold any sense of anachronism at bay. A different Chris, Pratt, has not yet proved that audiences love him as more than a harmless big lug. This cohort of guys is also not all that young. (I just learned that the endearing Channing Tatum is 41 years old; 41!) The actually young white male star with the most potential is Chalamet, and he comes off more like a species of exotic bird than a man with whom you might plausibly share a beer.

Damon’s upcoming two roles aren’t second dibs. They’re a classic big budget-indie twofer: “The Last Duel” and “Stillwater.” Somewhere to the good side of the knight Jean de Carrouges lies Bill Baker, a smart melding of good and bad Matts. It turns out that Tom McCarthy, the “Stillwater” director whose previous films include the Oscar-winning journalism drama “Spotlight,” is another of those directors who saw in Damon an image ready to be distorted. “It was important to get an actor who embodied an American ideal,” he says about casting his lead. “Which Matt brings to every role.” Starting there allowed McCarthy to “invert the American-hero story.” Bill Baker, he explains, is a man willing to do anything for his family, even when that is no longer legal and no longer right. The way that audiences are prone to trust Matt’s characters, even when they know what he’s doing is wrong, McCarthy says, was “interesting to lean into.”

Damon’s Baker is a quiet and subtly devastating turn. Affleck believes his friend is too humble to admit that “he’s as proud of that performance as any he’s given.” That performance is a result of untold hours of diligent preparation that manifests, Damon said, as countless “unconscious cues that tell you what kind of guy Bill Baker is.” There’s his specific Okie drawl, honed over long sessions with a dialect coach, his burly and lumbering middle-aged oil-rig worker’s physicality, his bushy goatee, wraparound shades, tucked-in flannel work shirt, jeans stiff with flame retardant. Most of all, there’s a true sense that Damon — a wealthy, Ivy-educated guy from the Northeast who fund-raised for Elizabeth Warren — is sitting deeply in the character’s skin. “Bill Baker’s life choices are not mine,” Damon said, “but it was my job to understand them.” To that end, Damon spent time shadowing oil-rig workers in Oklahoma, driving around with them, hanging out at their backyard barbecues, skeet-shooting with their kids and taking the ribbing in stride when one of those kids outshot Jason Bourne.

“Stillwater” is full of beautifully acted scenes, but there’s one that, to me, best captures the canny way that Matt Damon is able to use our good will for him as an emotional Trojan horse. Bill Baker enters the bedroom of someone he’s come to love, and to whom he has to say goodbye, most likely forever. Under a dirty baseball cap, his face admits the barest traces of sorrow: a few extra blinks, a barely perceptible tightening of the jaw. He inhales, deeply, just once. We all know and love men — husbands, fathers, brothers — who emote like this, which is to say with great difficulty. Baker nervously flicks his thumb against his index finger. He works his tongue against the inside of his lower lip, and speaks a few short lines: “You don’t want to talk to me. All right. I’m sorry. I’m so sorry. I love you.” The person to whom he’s speaking responds with silence. Baker bows his head, turns and stands for an aching instant in the doorway before walking away. In all the soft spaces around the words, Matt Damon breaks your heart. Never mind that the pain is his character’s own reckless fault.

Firmly into middle age and thick in the middle of his career, Damon has fully become the actor he hoped to be back at Rindge and Latin — one that Gene Hackman would, and does, admire. Hackman sent Damon a complimentary letter after seeing him in “The Informant!” But Damon has a different Hackman story to tell. In 1993, shortly after leaving Harvard, Damon found himself acting with the man himself. It was on “Geronimo,” and maybe “with” is a stretch. “I’m in one shot with him,” said Damon, who plays the film’s fifth lead. “Hackman plays General Crook, Jason Patric plays the first lieutenant and I’m the second lieutenant, Britton Davis. I’m eight horses back.” Watch the scene now, and it’s conspicuous how the baby-faced Damon, clad in his character’s U.S. Cavalryman’s costume, subtly guides his steed out from behind an Apache warrior on horseback. “I’m trying,” he explained, “to get into the frame so that I could be in the same shot as Hackman.” On that dusty day, Damon even got to meet the older actor when Hackman’s stand-in made an introduction. The two made small talk, and then, by way of saying goodbye, Hackman said, “Well, it’s great to meet you, Mark.” Remembering that moment now, Matt Damon flashed his movie-star smile, then slipped back into self-effacement. “It didn’t have to be the right name,” he said. “I was just happy to be there.”

Stylist: Karla Welch. Grooming: Matteo Silvi.

David Marchese is a staff writer for the magazine and the columnist for Talk. Recently he interviewed Alice Waters about being uncompromising; Neil deGrasse Tyson about how science might once again reign supreme; and Representative Adam Kinzinger about moral failure and Republicans. Christopher Anderson is the author of seven photographic books, including “Pia.” He lives in Paris.

Source: Read Full Article