Times Insider explains who we are and what we do and delivers behind-the-scenes insights into how our journalism comes together.

Talk to enough reporters and you will eventually hear the Story of Their Best Dateline.

For the uninitiated, datelines are the announcements at the beginning of an article that tell the reader, in all capital letters, when and where a journalist reported from. Once ubiquitous, and adorned with an actual date (hence the name), datelines have slowly disappeared at many news outlets; The New York Times recently announced that it would no longer affix them to digital articles in favor of a more plain-spoken approach and “a broader description of the reporting effort.” (Articles in the print edition of The Times still carry the traditional datelines in capital letters.)

OK, fine. But as a journalist who has reported all over the United States for the last three decades, I have always loved a dateline. I have savored and even sought out exotically named locations over the years. “ON SADDLEBACK MOUNTAIN, Calif.,” was a good one, for the tale of a Sierra Nevada fire lookout; “ABOARD THE PLASTIKI” was another, for an article about a catamaran made out of two-liter plastic bottles that somehow made it to Sydney, Australia, from San Francisco.

So when I began reporting on another stunt this month — a plan, by a British endurance athlete, to swim the entire 315-mile length of the Hudson River — I knew immediately where I wanted to go: Lake Tear of the Clouds, a small, elegantly named lake that is the source of the river, located high in the Adirondack Mountains of New York. The swimmer, Lewis Pugh, plans to begin his monthlong trek there on Aug. 13. And I wanted to see what he would see when he started downstream toward his final destination at New York City’s harbor.

The lake in question is south of Lake Placid, which seemed ideal for me: about a 2.5-hour drive from my home in Albany. I’d simply drive up and take a look.

Except you can’t drive to Lake Tear of the Clouds, something I discovered after I had already started my journey toward Lake Placid, when I stopped at a rest stop and consulted a magical information source known as Google.

Then the news got worse. “Reaching Lake Tear of the Clouds will require summiting a high peak, Mount Marcy, the tallest mountain in New York,” a website told me, before informing me of its distance: “8.7 miles, one way.”

As an ambivalent hiker — I prefer walks, or better yet, the couch — I generally never hike more than a few miles, preferably downhill. Not believing my first source, I quickly sought advice from other websites. All of them were distressingly similar and even downright cautionary: “a very hard, dangerous and strenuous trail”; “a physical and mental challenge”; “not for beginners.”

To say that I was unprepared was an understatement: I didn’t have boots or a backpack. I was wearing treadless running shoes and a pair of shorts from college. (Note: I am a long way out of college.) I didn’t have a map, a trail guide or even food. But I really wanted that dateline.

So it was that I continued on to Lake Placid. I stayed the night at a Main Street hotel, and the next morning, I ventured out to the trailhead after buying a glorified fanny pack, a big bottle of water and a collection of granola bars at a convenience store. I informed a friend — only half joking — to look on Mount Marcy if I went missing.

The first two miles were easy: flat, verdant, groomed. I got cocky. How hard could this be? Then I saw the boulders.

The Mount Marcy trail, as it turns out, is famously rocky, muddy and, after this summer’s torrential rains, often more like a stream than a path, complete with slick, huge slabs. Hopping from stone to stone along an increasingly steep terrain, I felt like I was doing a Paleolithic StairMaster. My knees and hips started to ache around Mile Four; my head around Mile Six.

I gave up trying to avoid puddles, sloshing in an ankle-deep slurry, nearly losing a shoe. I cursed roots and the trees that made them. I wondered about my choice of profession.

Finally, after nearly four hours, I saw the mountain’s summit, accessible only by an open-rock scramble at a 45-degree angle. It felt profoundly unsafe — and profoundly unfair. Worse yet, I knew that Lake Tear of the Clouds was even farther, another mile, on the far side of Mount Marcy. It would require going partly down the mountain’s southern slope to the lake and then back up the peak to catch the trail home.

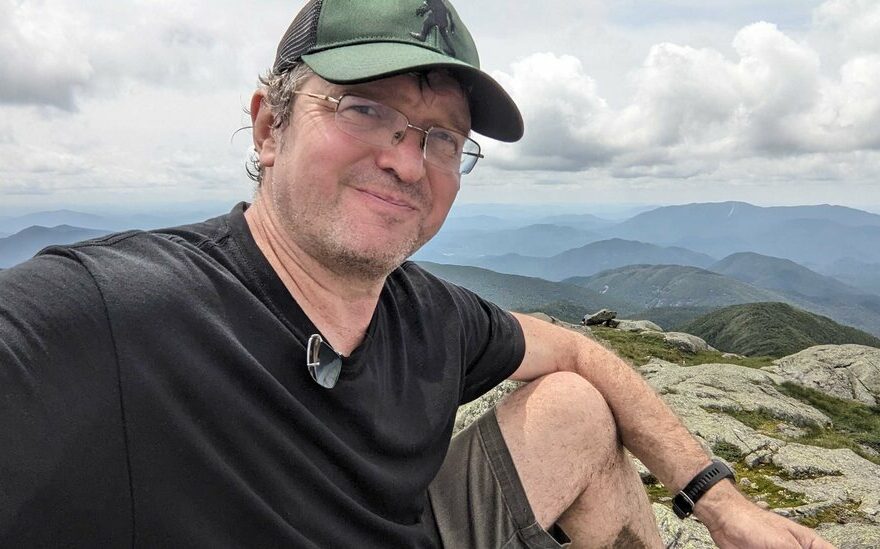

Still, when I finally panted my way to the summit, I could see why Mr. Pugh wanted to begin in the Adirondacks: His swim was meant to bring attention to the world’s rivers, the nature that surrounds them and the efforts to preserve both. And from atop Mount Marcy, there was evidence of that wonder all around: lush valleys, pristine peaks and fine horizons unblemished by human interference.

I took a moment — and a selfie — and gazed down at the little lake below with its delicious dateline. Even from a distance, I could appreciate its beauty: quiet, still and seemingly untouched. And, I knew then, just out of reach.

I plan to keep up with Mr. Pugh’s progress as he swims in August, but on this day, I was done. I turned around, exhausted and worried about getting back before dark — and in one piece. The dateline would have to be “ATOP MOUNT MARCY,” I decided. “LAKE TEAR OF THE CLOUDS” would have to wait for another story.

Or, perhaps, another hike.

Jesse McKinley is a Metro correspondent for The Times, with an emphasis on coverage of upstate New York. He previously served as bureau chief in Albany and San Francisco, as well as stints as a feature writer, theater columnist and Broadway reporter for the Culture desk. More about Jesse McKinley

Source: Read Full Article