Freezing winter in a place designed for frolicsome summer can be a doleful time. A case in point: the empty hotels, shuttered waterparks and endless fog banks of the Italian beach town that gives Ulrich Seidl’s challenging but riveting Berlin competition film its name. Along with the hazy gray shoreline and lonely iced-over thoroughfares, they’re the visual markers of a low season in which the “low” refers as much to mood as occupancy rates, though for the city’s tourist industry, it’s a gloom that will lift with the coming of spring. For Seidl’s film, a shiveringly precise slow burn that continues to burrow new tunnels in the mind long after it ends, no such renewal is in the cards. In “Rimini,” low season can always get lower.

The brilliantly named Richie Bravo (Austrian actor Michael Thomas giving such an astoundingly deep-dive performance it barely feels like performance at all) is a washed-up singer whose own high season is long behind him. Living alone in a rundown Rimini villa decorated outside in peeling paint and inside with beer bottles and posters of a thinner, younger Richie in his salad days, he supplements the meager income accrued from infrequent, sparsely-attended hotel club nights by sleeping with women from the audience for money. That these women are no longer in the first blush of youth does not seem to trouble Richie that much; he may be essentially a gigolo but he does, in his way, invest himself fully in the work. Indeed, an early encounter with regular “client” Annie (Claudia Martini) — shot in typically unembarrassed, unflinching fashion by the never-knowingly-prudish Seidl and his regular cinematographer Wolfgang Thaler — is so familiar and intimate, that it seems like maybe she’s just Richie’s girlfriend. Then she pays him.

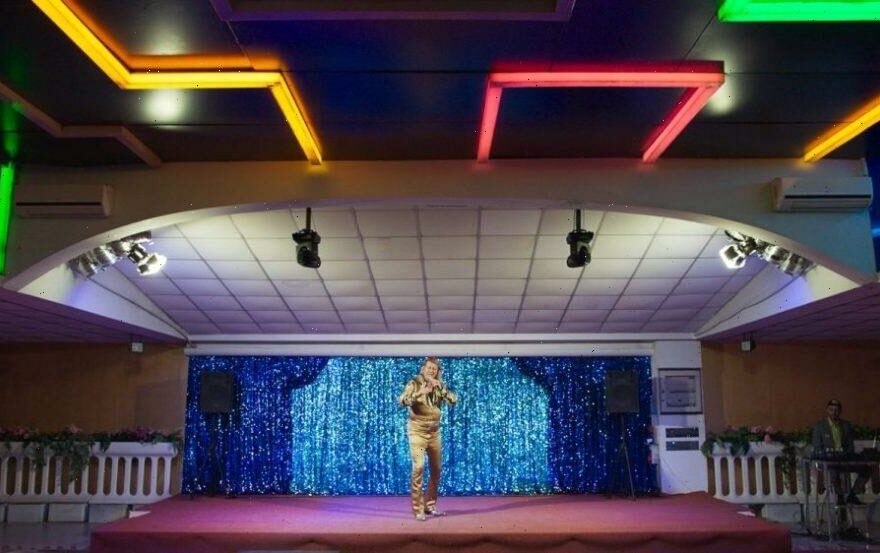

Even so, the initial characterization is almost affectionate, with Richie, again, so fully embodied by Thomas that “Rimini” can feel at times like a documentary given all-areas access to a real-life has-been pop star running on the fumes of past glories. A tragic figure, but not an unlikable one. Richie pours himself, waist-training spanx and all, into gaudy stagewear, embellished with massive belt buckle and snakeskin cowboy boots. He swigs vodka from a water bottle, because it leaves no smell on the breath. He sings schmaltzy schlanger music (somewhere between folk, country and traditional oom-pah-pah) to enthralled audiences of six or maybe 10 people — his pitch-perfectly awful songs are composed especially by Fritz Ostermayer and Herwig Zamernik with an earnestness that somehow makes their pathos all the more absurd. But Richie is sincere when he sings. He’s genial to those around him. And despite everything, a certain swaggery charisma still envelops him as snugly as his prized sealskin coat, a garment that deserves a co-star credit. For a time, it seems like this might be Seidl — again co-writing with his wife Veronika Franz — on unusually gentle form. Don’t get too comfortable.

There are several other strands to “Rimini,” the first in a diptych which will conclude with the upcoming “Sparta,” starring Richie’s brother Ewald (Georg Friedrich), whom we briefly meet in the prologue. There’s Richie’s father Ekkard (Hans-Michael Rehberg), a dementia patient often shown lost and helpless, spouting half-remembered Nazi propaganda, wandering the windowless corridors of his shabby Austrian nursing home. And there’s Richie’s daughter, Tessa (Tessa Göttlicher), a glowering blonde who shows up 18 years after Richie last saw her, to demand the back child support that Richie never paid. Not recognizing her, his first instinct is to flirt, and when he discovers his error, the ickiness of having just hit on his own child doesn’t seem to occur to him. But then, one of things that makes Richie so compelling is his almost heroic lack of self-criticism. Even as his attempts to scrounge up the cash lead him to ever more venal and vicious schemes, he seems able to forgive himself, on the rare occasion he divines there is something to forgive.

In the moment, during the more merciless stretches of Richie’s moral disintegration, or when simply observing, for an excoriating eternity, his addled father weeping at the window of his drab, cheaply furnished room, it can be hard to discern the broader picture being painted. But with a little distance from these endurance-test moments, patterns emerge from the mist: the little knots of dark-skinned Muslims who gather in increasing numbers in Richie’s peripheral vision; Tessa’s Arab boyfriend and his ever-expanding circle of friends, who encroach on the avowedly not-racist Richie’s life with the inevitability of a rising tide.

One moment with Ekkard sharpens the background blur of racially-charged unease to a razor point. The old man stands in his room alone, running through a drill dredged up from some corner of his misfiring memory, and as he practices his Hitler half-salute, he intones repeatedly “To each his due.” This is not, in the end, a tale of hubris brought low, or even of a tacky life staring down a long lens at a tawdry, dwindling death. Instead it’s a chilling parable about the sins of the father becoming the punishments of the son, and about the moral arc of the universe bending, across generations, toward the coldest justice imaginable.

Source: Read Full Article