Christopher Wheeldon knows how iconic Michael Jackson’s moves are to the world and to the entertainment industry, so when he stepped in as both director and choreographer for the Broadway show, now playing at the Neil Simon Theatre, he knew how important it was to get it right.

Not only did he have to honor fans, but he also had to put his stamp on the show.

Rich and Tone Talauega were brought on as part of the creative team. The two were dancers on Jackson’s HIStory World Tour and continued to dance and choreograph for Jackson once the tour ended. “They were the living, breathing encyclopedias of Michael’s movement language and his vocabulary,” Wheeldon says. But Wheeldon explains that he didn’t want a show that was a series of re-creations of Jackson’s numbers. “It needed to be seen through my lens, and [those iconic moves] were integrated with the overall choreography of the show, because the choreography is not just the steps. It is not just the movement. It’s how that movement then integrates with the story and how it becomes a part of the musical staging.”

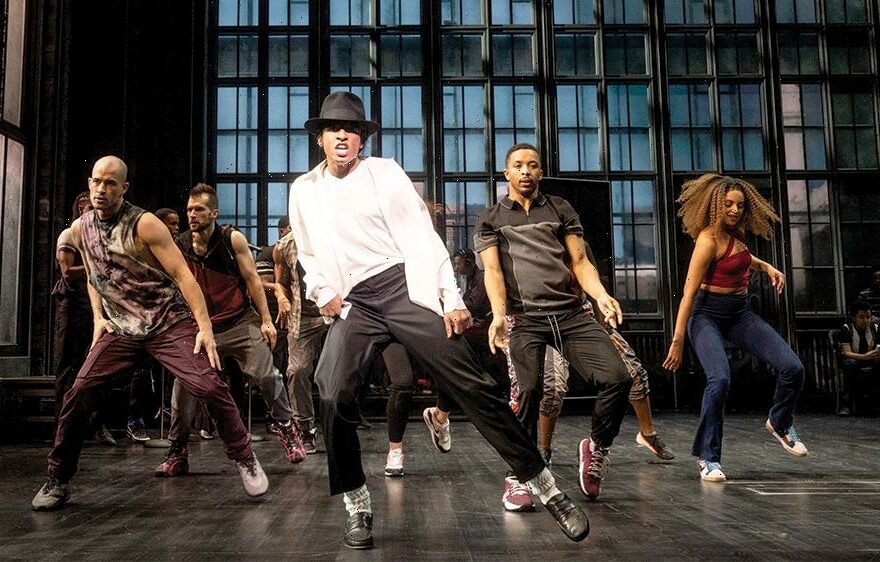

“MJ” is largely set in a rehearsal studio, with Myles Frost starring as Michael, who works on his songs as well as the ghosts of his past as he prepares to go on the Dangerous World Tour. With writer Lynn Nottage setting the show as a work in progress, “it gave us the freedom to just rehearse a number” that could evolve and “bore into the creativity” of Michael’s mind,” explains Wheeldon.

The rehearsal setting allowed him to breathe life into the songs in different ways. Act 2 of the show opens with “Billie Jean,” the biggest dance number in the musical. Wheeldon flexed his creative muscles as Michael meets those who influenced him: Bob Fosse, Fred Astaire and the Nicholas Brothers — Fayard and Harold. “That number was a study of how he built his movement and vocabulary, and how it blossomed into his most iconic music video, which was ‘Smooth Criminal.’”

Ultimately, a key to getting it right was the entrance. The number went through numerous iterations. Early in the workshopping process, Wheeldon had Frost enter as himself and turn into Michael with a hat and “an electric shock that emanates out from him.” While that visual was theatrical, it didn’t hit right.

In the end, a few boxes added levels to the set, and Wheeldon incorporated elements from the original “Beat It” video, such as the guitar solo. “We wanted to set up the world,” Wheeldon says. “Myles embodies Michael but doesn’t imitate him. He demands that [the audience] believe that he’s Michael.”

Source: Read Full Article