DAN HODGES: What Mum’s death taught me about the ailing NHS – and why better managers are as vital as nurses

As I write this, the bed in which my mother died is still downstairs. It’s sitting in the front room of her basement flat, with a nice view of the back garden and the flowers she used to love tending. In her own unique way. ‘I was told you have to talk to flowers,’ she once explained to me, ‘so I shout at them, ‘Grow, you buggers, grow!’ ‘

That bed – which was provided by the NHS – was a godsend. It meant she could spend her final days with us at home. It had a special mattress that massaged her legs and back, and prevented bedsores. It could be easily raised or reclined, so she could have a sip of coffee, or a sly cigarette. And, at the very end, it ensured she could rest in comfort and peace.

But she passed 21 days ago. And it’s still sitting there. Bringing comfort to no one.

Last week marked the 75th anniversary of the establishment of the NHS. Rishi Sunak praised it as a ‘cornerstone of our national life’. Sir Keir Starmer cited his own mother’s time working for and being treated by the service, and pledged: ‘I now see it as my job to get the NHS off life support and back to a clean bill of health.’

A service of celebration was held at Westminster Abbey.

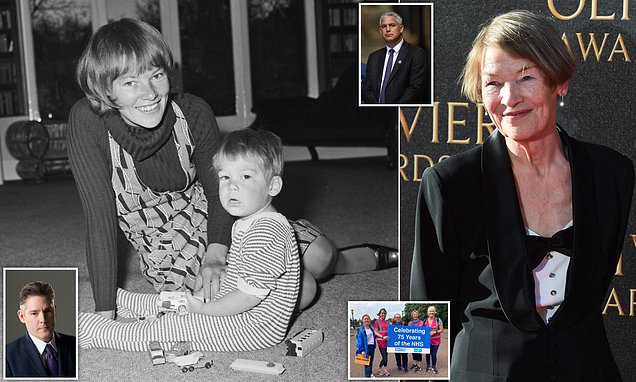

Glenda with her son Dan Hodges on the floor of a living room at home in London on 16th April 1971

My mother was then seen by a nurse, who started asking a long list of questions about why she had been admitted. I explained she’d been referred by the GP, and had a letter on my phone that he’d forwarded. She ignored me and continued asking the questions

But the most significant intervention came from Health Secretary Steve Barclay. In a series of briefings, he revealed a new plan to spend £2.4 billion on hundreds of thousands of new clinical staff, at the expense of more managers.

‘NHS to slash bureaucracy by recruiting doctors and nurses over pen-pushers’ screamed one headline.

And it will no doubt prove a popular policy. ‘We need more nurses and fewer managers’ is a mantra beloved by both politicians and voters.

But I’m not sure we actually do.

Several months ago, my mum’s GP phoned to tell me he’d just received some blood test results, and that I had to immediately take her to Lewisham A&E. After a lot of protesting, I bundled her into the car and down to the hospital. When we arrived, a security guard was sitting by the entrance.

We had to fill in a form and wait, I was told. After ten minutes I realised no one was moving. So I got up, ignored the guard, and walked up to the front desk. ‘Can I help you?’ the woman there asked. ‘Yes. Do you know you have a security guard out there who isn’t letting any of your patients in?’ I replied.

DAN HODGES: As I write this, the bed in which my mother died is still downstairs. It’s sitting in the front room of her basement flat, with a nice view of the back garden and the flowers she used to love tending

Over the past couple of years I’ve seen the NHS up close and personal. Cancer treatment. Heart treatment. Respiratory treatment. Palliative care. These sort of issues were commonplace

My mother was then seen by a nurse, who started asking a long list of questions about why she had been admitted. I explained she’d been referred by the GP, and had a letter on my phone that he’d forwarded. She ignored me and continued asking the questions.

Finally, I had to stand up and place my phone in front of the nurse. She relented, read the letter, and said: ‘Oh, I see.’

She told my mother to follow her, and walked her down to A&E, where she pointed to a chair and told her to wait. Then walked off. After sitting for another 30 minutes, my mother finally attracted the attention of the senior ward nurse. It then emerged they had a cubicle available to start examining and treating her, but no clinical staff had known she was there.

About an hour later, an orderly came to take her down for an X-ray. Five minutes later he was back.

‘That was quick,’ I said.

‘There were lots of people in the corridor. I couldn’t wheel her down there. I’ll try again later.’ he replied.

The most significant intervention came from Health Secretary Steve Barclay. In a series of briefings, he revealed a new plan to spend £2.4 billion on hundreds of thousands of new clinical staff, at the expense of more managers

READ MORE: Please stop calling us ‘junior’ doctors, whinge junior doctors: British Medical Association rules decades-old phrase is ‘demeaning’

The union said the infantilising phrase has been used to ‘devalue’ and ‘diminish’ their members’ contribution to the NHS and suppress their wages. Pictured, junior doctors on the picket line outside the Leicester Royal Infirmary

Over the past couple of years I’ve seen the NHS up close and personal. Cancer treatment. Heart treatment. Respiratory treatment. Palliative care. These sort of issues were commonplace. And they didn’t appear to primarily be down to a lack of resources. They seemed a product of a lack of basic management.

We talk about a National Health Service, but anyone who uses it frequently quickly becomes aware it isn’t a cohesive national organisation at all. A&E. The various specialist departments within the same hospital. Chemists. GPs. The ambulance service. None operate as an integrated entity. What we actually have is a series of independent national health silos.

Some of the care my mother received was outstanding. Brendan at Guy’s cancer department who – even though it wasn’t part of his job description – helped organise her end-of-life support. The three London ambulance ladies who cajoled and carried her to hospital one final time. The nijab-clad care assistants who patiently and tenderly washed and changed her.

But everyone who delivered that care seemed to be fighting a daily battle against the system they were serving.

After my mother was brought home, we were given pain relief that could be administered intravenously when it became hard for her to swallow.

When it came to the time to use it, I phoned the district nurse. ‘We can’t administer it without a referral from her hospice,’ I was told. I explained the hospice wasn’t returning my calls.

‘We can’t administer that medication,’ they repeated.

‘You’re the district nurse, and you can’t administer medication?’ I replied. I was then told to ring the Urgent Care nurse.

The Urgent Care nurse said they could administer it, if the right person was available.

‘The problem is a lot of our Urgent Care nurses aren’t actually nurses,’ she explained apologetically.

In some areas of the NHS there appears to be a total absence of coherent management. In others, an entire bureaucracy has been allowed to evolve that seems to have as its primary objective preventing patients accessing the appropriate care.

For example, we all know the challenges Covid posed for the NHS. But how much longer are we as a nation going to accept a situation where GPs’ receptionists continue to operate an unofficial triage service, making what in some instances will be life-and-death decisions, with little or no formal clinical training?

Last week marked the 75th anniversary of the establishment of the NHS. A service of celebration was held at Westminster Abbey (Pictured – Runners at a Parkrun event celebrating the 75th anniversary of the service)

In the last few months of my mother’s life, she was physically seen by her local GP twice

In the last few months of my mother’s life, she was physically seen by her local GP twice. Once, when they came to formally confirm she was receiving palliative care, thereby avoiding the requirement for an autopsy. And once to sign her death notice.

The 75th anniversary of the NHS is an appropriate moment to step back and take stock of our national health needs. But as we do that we should bear three things in mind.

The first is that everyone needs to realise that in 75 years’ time there will still be a National Health Service. Those who advocate tearing it down and starting again can save their breath.

Any political party that seeks power without pledging to protect and sustain it will be committing political suicide. The NHS, warts and all, is here to stay.

The second is that by holding commemorations of thanksgiving for the NHS, we are not venerating the service, but damning it.

It is impossible to have the serious national debate we need about how to reform and modernise our health system if we are literally deifying it.

The third is that we need to ditch this tired cliche about nurses and managers. The UK spends £180 billion on the NHS, and to overcome the ravages of the pandemic and political mismanagement we are going to have to spend a lot more.

But unless we manage that vast investment properly, we might as well throw every single pound on a bonfire. Getting high-quality managers is as vital for the future of our NHS as high-quality doctors, nurses and surgeons.

The man who was supposed to collect my mum’s bed finally arrived just as I was finishing this piece. But he’d been told he needed to repair it, not remove it, and didn’t have space in his van.

So it’s still sitting in the front room of her basement flat, with a nice view of the back garden and the flowers she used to love.

Source: Read Full Article