Everyone loves a heist movie. But from Rififi to Ocean’s Eleven, from Topkapi to Le Cercle Rouge, there’s never been a film about a major art theft quite like The Duke. Roger Michell’s comedy-drama about an eccentric working-class hero with a hyperactive social conscience, is only incidentally a crime story. Nevertheless, it tells us something special about the way the public relates to art – or at least the way the British public related to it in 1962.

Jim Broadbent’s spirited performance as Kempton Brunton, 61, a man whose sense of justice prevents him from holding a job, shows us a side of the United Kingdom that seems to have been swept away by era of Thatcherism, followed by Tony Blair’s version of swinging Britain. In retrospect, it’s difficult to say which of these regimes were most damaging to the social fabric, even if they came from opposite sides of the political fence.

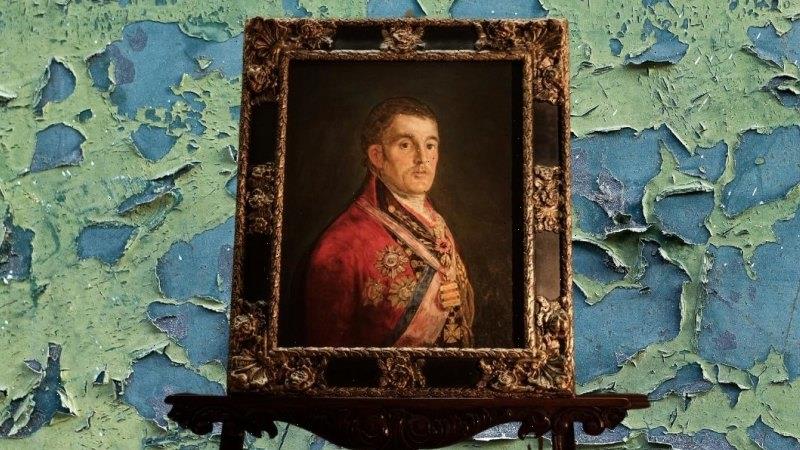

The stolen Duke of Wellington painting..

Disraeli once said Manchester was a greater achievement than Athens, but few people would make high-minded claims about Kempton’s hometown of Newcastle-upon-Tyne. In the Victorian era, Newcastle was a progressive city with an impressive array of Neo-classical buildings. By 1961 all we see are grim, red-brick, working-class enclaves. At the end of the street where the Bruntons live, huge factory chimneys are spewing smoke. One understands why Kenneth Branagh shot Belfast in black-and-white: because it makes poverty more aesthetically pleasing.

In the 1960s both Newcastle and Belfast enjoyed a strong sense of community that masked the shabbiness of everyday life. One reason is that many people had vivid memories of the Second World War, with its privations and sense of solidarity. In later years that community feeling would give way to the every-man-for-himself ethic that has dominated the 21st century. Look, for instance, at Ken Loach’s Sorry We Missed You (2019), also set in Newcastle – a story of a delivery man crushed by a relentless work routine, who gets sympathy from nobody.

Jim Broadbent plays a working-class mischief-maker at the centre of a major art theft.Credit:Nick Wall

On August 2, 1961, the National Gallery in London held a press conference to announce that Goya’s Portrait of the Duke of Wellington (1812-14), had been acquired for £140,000, matching the bid of a wealthy American collector at Sotheby’s. This was the equivalent of more than £3 million in today’s money, and a record price for Goya. The painting made headlines at the time, and again, 19 days later, after it had been stolen during a daring nocturnal break-in.

Almost four years later the thief would return the painting and surrender to the police. Brunton had sent five notes while he held the painting, his chief demand being that the government spend £140,000 on TV licences for old age pensioners as compensation for what he believed to be an unjust tax. In the film, Kempton is obsessed with the TV licence, even going to gaol for 13 days for refusing to pay it. (Incidentally, the TV licence in Britain today, is a flat fee of £159 per year).

Please note: If I’m to continue this discussion, I’m obliged to spoil the ending of the movie. The climax is Kempton’s trial at the Old Bailey, where he is ultimately acquitted for the theft of the painting but convicted of stealing the frame, which lands him in prison for a few months. He gets away with the art heist largely because of his bluff good humour, which makes it hard for anyone to see him as a master criminal. His motives are plainly altruistic rather than self-serving, and he uses the courtroom as a soapbox to say what’s wrong with British society.

Watching this film, I couldn’t help thinking that if Kempton were put on trial today he would have ended up with a conviction and a much stiffer sentence. Since 1965, we have witnessed a frantic escalation in the value of art and a complete transformation of social values.

In a 1989 essay titled Museum Visiting as a Cultural Phenomenon, Nick Merriman wrote: “between a third and a fifth of the British population can be estimated to be true non-visitors in the sense that they either never have visited a museum, or never will again.”

Damien Hirst’s work The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living.

Surveys taken around that time in Great Britain found that many working-class people seemed to believe such places “aren’t for the likes of us.” What we have seen since then is an expansion of popular interest in art provoked by two contradictory factors: a rising middle-class with the money to buy art and other luxuries, and a carnivalesque change in the way art is popularly perceived. It’s not only record prices and thefts that make headlines. In Britain (and most other places) today people are fascinated by the sheer silliness of so much contemporary art which seems to be tailor-made for the tabloids.

Sensation, the notorious 1997 Saatchi exhibition of YBAs (Young British Artists) set the tone, but there has been a steady stream of deliberately provocative works, before and after. Think of Damien Hirst’s shark in formaldehyde titled The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living (1991), or Tracey Emin’s unmade bed, My Bed (1998), which provided the rocket fuel for a wildly successful career. I could name dozens of equivalent works that never achieved such dazzling publicity.

Tracey Emin sits near her iconic art installation, My Bed, which was short-listed for the 1999 Turner Prize. Credit:Niklas Hallen

This kind of art brought a new audience to the museums – a low-brow crowd who came to laugh at the absurdities they’d seen in The Sun or The Mirror. They were accompanied by would-be intellectuals, eager to sing the praises of this “subversive” new art, which seemed to be made for Carry On movies rather than the Royal Academy. And then there were the entrepreneurs, the investors and nouveau riche collectors who – following Saatchi’s lead – could smell money.

Within a very short time, the Damiens and the Traceys were the new Academy. The rich collectors have bought YBA art by the truckload, and keep donating it to museums, which are obliged to accept these tax-deductible gifts or risk offending wealthy sponsors and donors. The dealers, meanwhile, have become multinational corporations, with branches in every major city. With money comes a new set of pretentions, and a new meanness. Artists’ work is protected by high-powered lawyers who will sue anyone that seems to be ripping them off or infringing what is loosely termed their intellectual property.

The art world today displays a casual disrespect for the art object combined with a serious love of money. In 2001, when Jake and Dinos Chapman decided to deface a set of Goya’s famous etchings, The Disasters of War, by doodling all over them, the value of the set increased dramatically. The message might have been: Vandalism pays. When a couple of Chinese performance artists had a pillow fight on Emin’s bed in 1999, they were released without charge. When a cleaner threw out a full ashtray that was actually a “sculpture” by Hirst, he laughed and made another one. When Saatchi sold the infamous shark for a reputed US$12 million to hedge fund manager, Steve Cohen, in 2004, Hirst commissioned a new version, as the original had decayed into a ghastly mess. Banksy uses a hidden device to shred one of his works at auction and its value skyrockets.

Nevertheless, if a Brunton managed to steal a Goya from the National Gallery today, one suspects he would receive a stiff prison sentence, as it has been impressed upon the public mind that art is a highly valuable commodity which may sell for sums exceeding $100 million.

If a latter-day Kempton defaced a Damien Hirst it might be passed off as a gag – because this kind of art, as everyone tacitly accepts, is a stunt in its own right. Such stunts may be bought and sold by rich collectors for astonishing sums, but there’s a general feeling that it’s all a game – not “real” art, like the stuff on the walls of the National Gallery.

And so we arrive at a world in which the first thing people ask about a work of art is: “What’s it worth?” The Old Masters are respected but seen as a bit boring, while contemporary art is often viewed as a joke or entertainment. One sees the results of this in the way rooms in art galleries previously hung according to chronology or place of origin are now increasingly mixed up, based on mysterious shared affinities. These garbled hangs, in which the curator plays the role of artist, were once a daring experiment, now they are becoming a convention.

It all points to a radical loss of confidence in the historical role of the art museum, once viewed as a place in which the best and most significant art of the past and present was preserved for the public and future generations. Museums are losing their sense of identity in the scramble to attract new audiences and sponsors, and the desperate desire to appear socially progressive. It may be that in the future those who say art museums are “not for the likes of us”, will be people with the greatest love and respect for art.

A cultural guide to going out and loving your city. Sign up to our Culture Fix newsletter here.

To read more from Spectrum, visit our page here.

Most Viewed in Culture

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article