IN CERTAIN FAMILIES, there’s only room for one storyteller, and in mine, it was my grandfather. Grandpa O’Grady was always the hero of the anecdotes he told of his Depression-era childhood, which were about things like eating onions from the food donation box raw, out of hand, like apples, or driving his mother home from church after his father, who liked his whiskey, passed out in the pew. These stories, with their inevitable triumph-over-odds arc, were our firmament, but they also felt slightly apocryphal; when he told them, we were aware of witnessing a kind of performance, and that was probably why they gave us the giggles: the rhetorical flourish of certain repeated details — the juice of the raw onion “dribbling down his chin”; driving the car “in first gear the whole way.” At the same time, we sensed something real in his need to re-enact the same memories again and again in his effort to reconcile the genuine hardships of his past with a dissonant present embodied in his young grandchildren, indifferent to their apple-eating good fortune.

While touring preschools for my daughter, I spotted a construction-paper poster taped to a library wall: “Fiction = not true,” was written on it in Magic Marker. “Nonfiction = true.” Clearly destined for the darkroom of Instagram opportunism, the poster seemed to hark back to the days when binary thinking was enough, when, at least for men like my grandfather, the world was thus organized: People were either good or bad, their actions right or wrong; stories were either true or not true, and always freighted with a clear moral argument. Meanwhile, here in 2021, my 5-year-old had already grasped the way in which animated frogs might speak ageless truths, while the flesh-and-blood figures in her life might color outside the lines. The fantasy that you can say something so perfectly and with such absolute authority that it never needs another version told from another point of view, as my grandfather might have believed, is long over. Now that self-authorship is a form of digital hobby, we’re savvy to the fact that our versions of events tend to be freighted with self-interest (“my truth,” “my journey”), that there’s a power dynamic at play in who owns the narrative and that our experiences don’t generally have a clear takeaway unless we frame them just so. “Memory itself is a form of architecture,” said the artist Louise Bourgeois, whose autobiographical sculpture emerged late last century in all kinds of shapes, most iconically that of a 30-foot-tall cast-bronze spider. There’s an art to memory, and our personal stories become symbolic over time, the juicy onions and ghostly, maternal arachnids emblematic of a more complex whole.

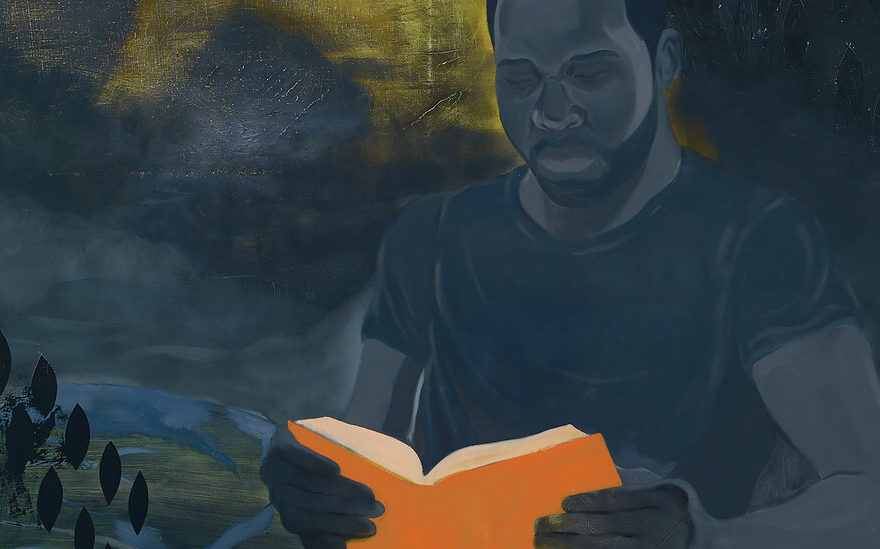

Memory is also identity, and for those historically cast to the margins of our national stories, or those who grew up as the silent daughters or queer kids at the family dinner table, seizing control of one’s narrative has a particular power. I often think I would never have become a critic had dissent been encouraged in the younger generation in my house, a feeling to which a lot of writers probably relate. For many of us, writing is a solace, a method of self-sorting, and the ability to share a point of view without being shut down or condescended to has even more weight for those who haven’t always been let into the conversation. This is why memoirs by women, immigrants and minorities of all kinds are often about the effort of becoming a coherent self within larger forces — forces that are inevitably classed, gendered and raced. For those whose perspectives are missing in the canons and histories we learned in school — who have been long ensnared in the cultural narratives of those more powerful — the memoir has served as a site of redress, a space in which to turn the tables, to make their experiences visible and their stories heard: a passage not only into literature but into a larger acceptance. Our most canonical memoirs, including Maya Angelou’s 1969 “I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings,” in which the author describes a childhood shaped by bigotry and books; Paul Monette’s 1992 “Becoming a Man,” a chronicle of the gay rights activist’s struggle to come out; or Mary Karr’s 1995 “The Liars’ Club,” about the writer’s experiences growing up poor in small-town Texas, humanized people who weren’t previously given much of a voice with what felt like unfiltered immediacy, arriving with descriptors like “unsparing” and “unflinching.”

We were unspared; we flinched. Part of these memoirs’ popularity was due to readers’ understanding of them as hard-won, brutally honest acts of self-assertion on the part of their authors, outsiders whose experiences hadn’t really been recognized by the culture at large. Yet that popularity is anything but unequivocal for those who see memoir as an act of exposure as spectacle, a revealing of painful, intimate moments of one’s life to a wider gaze. For the disenfranchised, writing one’s own story has never been as simple as stringing together life-defining events on a kind of grail quest for self-acceptance and healing. The expectation, largely publisher-driven, that a white, middle-class literary readership will be catered to makes the confessional-as-entertainment mode especially compromising for those whom literature and society haven’t always heard or valued. And, as anyone who has ever been talked over or silenced for airing a dissenting view knows, “having a voice” is no assurance of being taken seriously. Our words — whether spoken at a work meeting or a dinner party, or written on a page — can’t really be separated from how others perceive our bodies. In our public lives, in our private lives, we’re never just ourselves but also our historic selves. Just how much a well-crafted personal story might really shift those perceptions is increasingly — and fascinatingly — up for question.

IT’S NOT A coincidence that memoir surged in popularity in the late 1980s and 1990s — with books like Vivian Gornick’s 1987 “Fierce Attachments” and Elizabeth Wurtzel’s 1994 “Prozac Nation” — around the time that psychotherapy felt like it had become a commonplace middle-class pursuit (and with it, a desire to see ourselves as the protagonists of our own lives). Their intimacy and power were undeniable: Reading them, one felt like one was being let in on shameful secrets — of the sort that create generational divides, in Gornick’s case, or a stigma around mental health issues, in Wurtzel’s; the shame metabolized in the writing. In the current century, with our emphasis on “authenticity,” the form has taken a bit of a critical beating, increasingly prefaced by disclaimers, admissions of composite characters and reconstructed dialogue. Then there was the disconcerting fact that writers were receiving six-figure advances for their tales of subversive private lives or terrible childhoods (one of the weirder ironies of publishing a memoir is that by claiming ownership of one’s own story, one no longer quite owns it). In short, the memoir had become yet another thing people dismiss as performative or embarrassingly indiscreet, the solipsistic grandpa at literature’s table — never mind that this was precisely what many of us found irresistible about them. Meanwhile, a cooler, more highbrow literary form — the autofictional novel — has arisen to meet our craving for intimacy, blurring author and protagonist with a veneer of transparency, or at least the performance of it, while maintaining the plausible deniability of fiction: Fiction = not true.

And yet memoir has never really dwindled in popularity but has instead evolved into highly specialized, self-interrogating shapes. A cursory glance at my bookshelf affirms this, crammed as it is with recent examples, including grief memoirs (Michelle Zauner’s 2021 “Crying in H Mart”), graphic memoirs (Alison Bechdel’s 2021 “The Secret to Superhuman Strength”), memoirs grounded in urban history (Sarah Broom’s 2019 “The Yellow House”) or critical theory (Maggie Nelson’s 2015 “The Argonauts”), memoirs elucidating trauma, from abusive forms of love (Carmen Maria Machado’s 2019 “In the Dream House”; Kiese Laymon’s 2018 “Heavy”) to the painful dislocations of migration (Jenny Erpenbeck’s 2020 “Not a Novel”) — even memoirs in the guise of literary biography (Jenn Shapland’s 2020 “My Autobiography of Carson McCullers”). All are risk-taking in form, defying pat genre labels. Their authors all believe in the ability to write oneself closer to self-knowledge, in the value of making the effort to understand oneself in a larger context. At the same time, these books acknowledge that our identities are all — to a certain extent — crafted, works of imagination. The most famous memoir ever written, Anne Frank’s 1947 “The Diary of a Young Girl,” its author’s account of hiding during World War II, was repeatedly revised by Frank in the hope that it would one day be printed, as Francine Prose notes in her 2009 “Anne Frank: The Book, the Life, the Afterlife”; this is what makes it literature, and no less immediate, true or valuable for it.

The new literary memoir considers the quandary of writing one, seeding its own ambiguity by contending with the limits of conventional forms to address the complication and constraints of identity. “I wanted to write a lie,” Laymon writes in the first pages of “Heavy.” “I wanted to create a fantastic literary spectacle.” Instead of fulfilling our expectation of uplift, he gives us a sense of the particular weight of a particular history and of a particular kind of mother love. For Machado, writing “In the Dream House” entailed taking on a cultural history filled with caricatures of queer villains and deconstructing the traditional ways in which domestic abuse has been told. “I broke the stories down,” Machado writes, “because I was breaking down and didn’t know what else to do.” In memoirs like these, lines are carefully drawn between having skin in the game and opening a vein, between the need to be seen and the dread of being seen as a token. They acknowledge that we all know there’s no moral to the story. By looking disabusingly upon the possibility of real catharsis, and on empathy as something that can be lastingly earned in a few hundred pages, they spotlight, rather than shadow, the fear of writing to fulfill an expectation of how one’s story should go.

HISTORIES OF MEMOIR tend to begin with St. Augustine’s “Confessions” around 397 A.D., but there’s no doubt that the form enjoys a particular centrality in our individualistic country. The impulse to “celebrate myself and sing myself, and what I assume you shall assume,” as Walt Whitman wrote in 1892, somehow feels endemic to our nation of competing origin stories, and the battle to own a national narrative continues today. Whitman urged us to “no longer take things at second and third hand,” but to “listen to all sides and filter them from your self.” In fact Americans were already doing just that, in proto-memoir forms like Puritan spiritual testimonies, captivity stories, narratives of the enslaved and immigrant oral histories. Often, works of this type share common threads: an element of educating while entertaining and a moral argument. Memoir as polemic has a long tradition in the United States, and it includes everything from the minister’s wife Mary Rowlandson’s 1682 account of being held for 11 weeks by Native Americans — a best seller of its time, written with breathless detail and clear Christian precepts, urging readers to see their sufferings as trials to which they are subjected by God — to Kate Bornstein’s 1994 “Gender Outlaw,” which mixes theory, personal narrative and outrageous humor to make the then-radical case that gender might not, in fact, be binary at all. Memoir has turned out to be the perfect genre for Americans, perfected by Americans, a nation of oppositions narrating themselves into existence.

Not everyone had this luxury, of course: The great frustration with our written archives is in their limitations, in the perspectives that cannot be found within them, particularly those of Native Americans and enslaved people. “How does one tell impossible stories?” the American historian Saidiya Hartman asks in her 2008 essay “Venus in Two Acts,” which describes the problematic history of two girls on the middle passage from Africa: problematic not because we aren’t certain of their existence — we are, because the captain of the slave ship on which they were killed was tried, in 1792, for their murder, the charges recorded in trial documents, which also recorded his acquittal — but because we have no way of accessing their voices, experiences, hopes, fears or even their names. No autobiographical narrative of a female captive who survived the middle passage exists, Hartman explains, and to try to conjure one would be to “trespass the boundaries of the archive,” as she puts it. The need to tell true stories of those voices requires pushing back against the confines of history, creating speculative arguments “to imagine what cannot be verified,” as Hartman does.

For an immigrant in a new country, telling one’s story might feel like a life buoy; for a formerly enslaved person, legibility was a matter of life and death. Written in part to convince a white public that slavery as an institution was immoral, books by people who had been enslaved were often — as in 1845’s “Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave,” and Harriet Jacobs’s 1861 “Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl,” which recalls hiding for seven years in a room too small to stand up in — composed as arguments for the abolition movement, to be read not only as personal, historical accounts but as representative experiences of their race, a kind of proof of humanity. Often, Toni Morrison writes in her 1995 essay “The Site of Memory,” their authors stopped short of describing certain horrors, fearing that white audiences, even sympathetic ones, would be turned off. Little indulgence is given to the inner life. Morrison herself was inspired by them to write her most famous novel, 1987’s “Beloved,” using what she called “literary archaeology” in drawing from these personal histories and inhabiting them with something of her own emotional memories to create fictional characters. Morrison, notably, never wrote a memoir; in 2012, she admitted that she’d canceled a contract to do just that, claiming that her life wasn’t interesting enough, though one wonders if she simply preferred not to invite that level of scrutiny into her private life (as an editor at Random House, she had edited the autobiographies of Angela Davis and Muhummad Ali). Or perhaps she knew that she’d already conveyed her most urgent emotional truths in her novels and essays, and knew that their impact had been felt just as profoundly as if they had been her own personal history. In a 1998 interview, she said of the massive audience her works had attracted: “I stood at the border, stood at the edge and claimed it as central, claimed it as central and let the rest of the world move over to where I was.”

The expectation of palatability to a white, middle-class audience persisted well into the 20th century. When Richard Wright’s 1945 autobiography, “Black Boy,” was originally published, it was cut down by half — the more frank passages expurgated — in order to please the Book-of-the-Month Club. (In 1991, a restored version was published.) As Hartman has written, the afterlife of slavery is not only a political and social problem but an aesthetic one. Or as the critic Margo Jefferson puts it in “Negroland,” her 2015 memoir of growing up in an elite Black community, where she was tasked with being an exemplar of her race, an expectation that exacted a profound psychic cost: “How do you adapt your singular, willful self to so much history and myth? So much glory, banality, honor and betrayal?”

The tenuous relationship between memory and imagination, once seen as a failing of the genre, becomes a kind of asset in this light: It takes not only truth but vision to counter our culture’s received ideas, to invent ourselves in our own way, on our own terms, against what Hartman calls “the silence in the archives.” It requires new forms. Jefferson wraps her story in a larger social history of the Black American upper class, making explicit her role as both a character in and a curator of her story by breaking through the book’s narrative scaffolding to address her readers. Rereading it, I’m reminded that the outsider memoir hasn’t really been given credit for breaking new aesthetic ground in the way we tell coming-of-age stories. Think of Joe Brainard’s 1975 “I Remember,” which recalls his experiences as a creative queer kid in the Midwest in the 1940s; it remains as freshly original today, something in its sensual, associative fragments perfectly capturing the eerily immediate presence of our pasts. Or Maxine Hong Kingston’s 1976 “The Woman Warrior: Memoirs of a Girlhood Among Ghosts,” in which the author’s mother tells her stories drawn from Chinese lore. Moving between the family laundry business in California and the realm of myth, Kingston evokes the way in which the vivid worlds our immigrant minds inhabit might coexist with more mundane realities our bodies do. Or the many art memoirs, including David Wojnarowicz’s 1991 “Close to the Knives,” which prefigured not only episodic memoirs but memoiristic visual art, and Yvonne Rainer’s 2006 instant classic, “Feelings Are Facts,” the jagged disjunctions of the prose not unlike the fractures of a life lived for art’s sake, with correspondingly high stakes.

One measure of the tremendous power of personal narrative, with its centering of authority with the writer, is how threatening it can be to others: Ask anyone who has written one. Having published one of the most celebrated memoirs ever written, Kingston found herself disparaged by a handful of Chinese American critics who believed that she was unfaithfully or negatively representing the culture. In a 1982 essay, Kingston responds, taking white reviewers to task for their stereotyped readings of her work while also addressing Chinese American critics who implied that she had maligned her own race. “Why must I ‘represent’ anyone besides myself?” Kingston asks. I remember the bitter antagonism that greeted Frank McCourt’s wildly popular 1996 memoir, “Angela’s Ashes,” which recalls an impoverished childhood in the Limerick slums in the 1940s all too vividly for Irish Americans who preferred a softer lens on their heritage. It surely wasn’t that bad, the thinking went, or if it was, we shouldn’t embarrass the clan by affirming the stereotypes. Never mind that McCourt not only acknowledges them but also transcends them.

How does one avoid being reduced to a symbol? At the level of language, to start. As a college student, Laymon discovered the author Toni Cade Bambara and realized that writing something true “required loads of unsentimental explorations of Black love. It required an acceptance of our strange. And mostly, it required a commitment to new structures, not reformation.” Another approach is to explicitly define one’s audience. Laymon addresses his narrative to his mother. Ta-Nahesi Coates’s 2015 memoir, “Between the World and Me,” takes the form of a letter to his son, dispatching with the default expectations of whom the author is writing for. The idea of writing as cathartic release is skeptically looked upon in most of these new memoirs. The body has memory, and it carries more than its weight, as Claudia Rankine, whose 2014 “Citizen: An American Lyric,” which toggles between her own experiences and those of other Black Americans, including Serena Williams, reminds us. Which is not to say that telling one’s story feels any less urgent today; it’s just that we no longer believe in emotional exorcism. I often think of Jesmyn Ward’s description of how she felt writing her 2013 memoir, “Men We Reaped,” which tells two stories, one — of the author’s childhood in Mississippi and journey to becoming a writer — in chronological order, the other — of the deaths of her brother, cousin and friends — in reverse, the two narratives converging at their emotional apex, the grieving self and the expressive self meeting at a painful join: “You hear about bones having to be re-broken and reset so they can heal in healthier ways, and that’s the way I think about what the memoir did to me,” Ward explained in a 2013 interview with The Writer magazine. “I’ll still have scars, of course, because you can’t erase what happened, but I’m hoping that they will be a little cleaner.”

MEMOIR INVITES IDENTIFICATION with the author up until the point that it — inevitably — disappoints it. I think of my queer and trans students and friends who were galvanized by Nelson’s “The Argonauts,” even where their ideas diverged from hers. What they found, in addition to an acknowledgment of their experiences, was a model of a certain way of being in the world, a mode of interrogating the thing one is in the midst of experiencing — in Nelson’s case, creating a family with her gender-fluid partner, who was transitioning at the same time the author was pregnant. That open questioning allowed space for multiple takes, for imperfection, for the kind of self-reflection that might, in fact, enlarge us. (Notably, for her new book, “On Freedom: Four Songs of Care and Constraint,” released this month, she moved away from memoir.) Pregnant myself at the time “The Argonauts” was published, I smiled in recognition when Nelson asks: “Is there something inherently queer about pregnancy itself, insofar as it profoundly alters one’s ‘normal’ state, and occasions a radical intimacy with — and radical alienation from — one’s body? How can an experience so profoundly strange and wild and transformative also symbolize or enact the ultimate conformity?”

Memoir, too, has a strangely doubled effect, both complicating and making accessible entire lives and histories, immersing us in another soul and skin. By equipping us to do without them, as the best of the form often do, opening our eyes to experiences we’ll never unfeel and ways of thinking we’ll never unthink, they have a way of lingering with us. In making a case for our singularity and alterity, they make us legible, even relatable or “normal.” In pursuit of internal concord, they reach across the aisle. Nelson anticipates the way in which people will identify with her, writing, “I don’t want to represent anything. At the same time, every word that I write could be read as some kind of defense, or assertion of value, of whatever it is that I am, whatever viewpoint it is that I ostensibly have to offer, whatever I’ve lived. … That’s part of the horror of speaking, of writing. There is nowhere to hide.” But that, too, is part of our human paradox: In our effort to be seen as individual, we find commonality; despite our fear of judgment, our need to matter prevails.

Source: Read Full Article