As the 1970s dawned, the Beach Boys were in crisis.

The quintessential American rock band of the ’60s, whose sun-kissed harmonies and string of girls-cars-and-surf hits soundtracked the myth of California as paradise, had lost its lock on the charts. Brian Wilson, its leader, was withdrawn and unstable after an attempt at a super-ambitious album, “Smile,” collapsed in 1967. Facing irrelevance, the band even considered changing its name, to simply Beach.

“When you put out a record and it’s not successful like you’re used to, you start questioning yourself,” the vocalist Mike Love said recently. “Are you doing things right? What do we need to change?”

What the Beach Boys did next is the focus of a new boxed set, “Feel Flows: The Sunflower & Surf’s Up Sessions, 1969-1971.” In purely commercial terms, the band’s first two albums of the ’70s were duds. “Sunflower” (1970) stalled at No. 151 on the Billboard chart, a new low. “Surf’s Up” (1971) fared better, at No. 29, thanks to its semilegendary title song. Neither contained any hits.

Yet in 135 tracks, most of them previously unreleased, “Feel Flows” makes a compelling case for this as a crucial but underexamined period of Beach Boys history, a time of experimentation and reinvention that highlighted the talents of the entire band. Along with the 1973 album “Holland,” it may have been the Beach Boys’ last truly progressive phase, before a mid-decade veer into nostalgic conservatism.

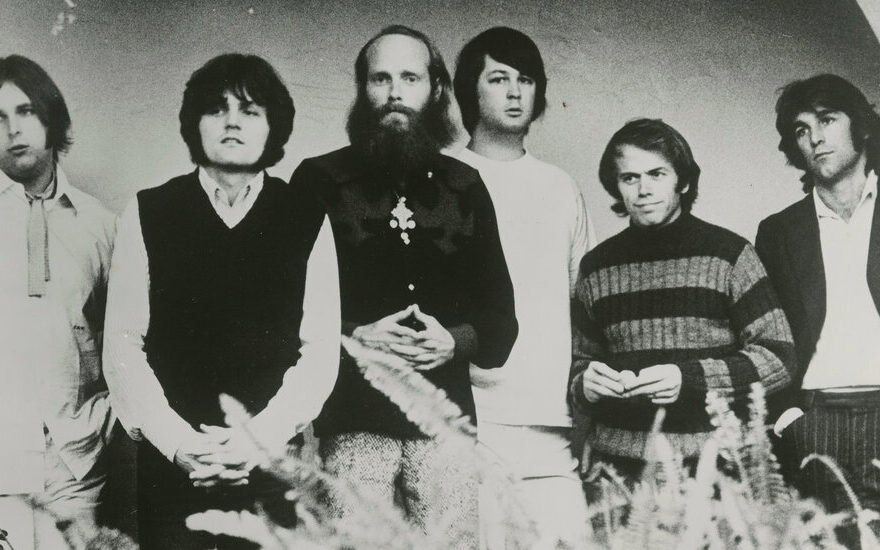

For more than 50 years, the story of the Beach Boys has been told primarily through Brian Wilson: his vision, his triumphs, his struggles. “Feel Flows” suggests a different path through the contributions of the wider group, particularly Wilson’s two younger brothers, Carl and Dennis, who made huge strides as songwriters and in the studio.

That was by necessity, since Brian Wilson was increasingly absent. The band recorded most of “Sunflower” and “Surf’s Up” in a studio built in Wilson’s Los Angeles home — directly below his bedroom, where Wilson spent most of his time, occasionally darting downstairs when inspiration struck.

“Brian really was the Beach Boys — is, was, has been, shall be,” said Al Jardine, the rhythm guitar player, who still tours with Wilson. “He started to retreat from the Beach Boy experience, and the rest of us were still catching up.”

In an interview, Brian Wilson said his withdrawal ended up having a positive effect. “It made the band want to play better and harder,” he said.

Some songs on “Sunflower,” like “Add Some Music to Your Day,” have a bit of the old Beach Boys magic, with crisp harmonies and “dum-dum-bee-doo” backup parts, but they failed to catch on. Jardine recalled the band feeling reinvigorated after recording that track, only to be crushed when radio stations ignored it.

By the time the Beach Boys began working on what became “Sunflower,” the band was nearing the end of a deal with its longtime label, Capitol, and had not had a significant hit since “Good Vibrations” in 1966. Rock was evolving fast, but the Beach Boys — now at the Reprise label, part of Warner Bros. — were perceived as being stuck in the past.

“We were probably just seen as the surfer Doris Days, the surfing Kingston Trio,” said Bruce Johnston, the bassist and vocalist who had taken Brian’s place on tour and was starting to write songs for its albums. “It wasn’t ‘cool, my brother’ to play the Beach Boys for a while,” he added.

The Beach Boys’ reputation wasn’t helped by Dennis Wilson’s association with Charles Manson and his cult, whose killing spree and subsequent trial were front-page news at the time.

Separated from the context of early ’70s radio, though, “Sunflower” has striking highlights, like “All I Wanna Do,” with murky currents of guitars and electronics that seem like a harbinger of chillwave indie-rock. Brian Wilson said that “Forever,” written by Dennis and Gregg Jakobson — a simple, tender ballad with a mournful undertow — is his favorite Beach Boys song by another member.

“It’s just a beautiful tune,” Brian added, sounding wistful. Dennis drowned in the ocean in 1983, at age 39, and Carl died of lung cancer in 1998, at 51.

If “Feel Flows” has a central character, it is Carl Wilson. The lead guitarist and youngest brother, he was only 15 when the band released its first album, in 1962. And although he was the band’s de facto leader on tour — Brian had quit the road by early 1965 to concentrate on recording — Carl had always seemed the quietest, humblest Beach Boy, known mainly for his angelic lead vocal on “God Only Knows,” from the album “Pet Sounds.” (Dennis, the drummer, was the rowdy heartthrob and the only real surfer of the bunch.)

By “Sunflower,” Carl was taking a stronger role in the studio, and he contributed two of the most powerful tracks on “Surf’s Up”: “Long Promised Road,” a gospel-like hymn of perseverance, and the pulsating, mysterious “Feel Flows.”

Those songs had lyrics by Jack Rieley, then the group’s manager, who tried to whip the band into contemporary relevancy by getting the members to ditch old gimmicks like wearing matching outfits onstage. He also encouraged socially conscious lyrics, which the band took to heart, though it yielded some howlers. (From the environmental alarm “Don’t Go Near the Water”: “Toothpaste and soap will make our oceans a bubble bath/So let’s avoid an ecological aftermath.”)

The song “Feel Flows,” despite purple lyrics (“Unfolding enveloping missiles of soul/Recall senses sadly”), has a strong emotional pull — and an out-there flute solo by the jazz luminary Charles Lloyd — that has made it a favorite among Beach Boys connoisseurs. The director Cameron Crowe used it in the closing credits of “Almost Famous,” both as a period nugget and for how the song reflected the film’s ending theme of openhearted reconciliation.

“It’s the feeling that you get of peaceful acknowledgment of the human adventure,” Crowe said. “It’s that feeling that great music gives you, which is that spot way above it all, seeing the whole shape of everything and coming to peace with it all.”

The boxed set, produced by Mark Linett and Alan Boyd, who won Grammys for their work on “The Smile Sessions” from 2011, has some gorgeous extras, like an early version of Love’s “Big Sur” that is very different from the one that later appeared on “Holland.” There are also oddities like “My Solution,” a monster-movie novelty recorded by Brian on Halloween 1970, and a 40-second quotation from the Beatles’ “You Never Give Me Your Money,” performed on electric piano — but by whom? The producers think it was Johnston, who said he has no idea.

Johnston, who started to come into his own as a songwriter during this time with songs like “Disney Girls (1957),” recalls the “Sunflower” sessions fondly, as proof of “how friends can do something wonderful together.” (Soon after that album, he left the Beach Boys for a time, and won song of the year at the Grammys in 1977 for “I Write the Songs,” a No. 1 hit for Barry Manilow.)

Still, the standouts on “Feel Flows” remain the two Brian Wilson songs that closed the “Surf’s Up” album: “’Til I Die,” a haunting meditation on mortality, and the title track, which by its release had acquired mythic status as Wilson’s ultimate lost masterpiece. The song was written with the lyricist Van Dyke Parks during the “Smile” sessions, in 1966, and Wilson played a version of it at the piano on “Inside Pop: The Rock Revolution,” a 1967 television documentary hosted by Leonard Bernstein. After that, the song vanished, even though many other “Smile”-era tracks had been repurposed for subsequent albums.

Releasing the track in 1971 was also a calculated branding move, turning surfing lingo on its head to telegraph that the band was moving on. Completing it in the studio was a technical feat that involved Carl singing the lead for the song’s first movement, which had been produced by Brian and recorded with a full complement of studio musicians; the second half was drawn from a solo piano and vocal recording by Brian, with the group adding expansive vocals in the coda.

“Surf’s Up” is perhaps the most analyzed song in Brian Wilson’s oeuvre; Bernstein, on “Inside Pop,” said it was “too complex to get all of, first time around.” Its melody is like the arduous scaling of a mountain toward a glorious peak, and Parks’s lyrics suggest an allegory about the challenge facing pop music — and the entire 1960s generation — in being taken seriously.

“At that point it represented exploration, a desire to get out of the box,” Parks said in an interview. “It was rebellion and liberation and confirmation, all wrapped up in a melodic wonderment.”

By 1971, a polemic about rock as high art — after the Beatles’ “Sgt. Pepper” and “Abbey Road,” after the Who’s “Tommy” — may have seemed moot. Speaking now, Wilson said it came out “right on time,” and it still feels like a philosophical maze.

Last year, the Beach Boys signed a reported nine-figure deal with Iconic Artists Group, founded by the industry power broker Irving Azoff, with the band selling the majority of its intellectual property rights, including their trademarks and the rights to much of their music. It is one of a string of high-profile catalog deals recently — Bob Dylan, Paul Simon, Neil Young and members of Fleetwood Mac have also made agreements — that are changing the financial game for older artists. Executives at Iconic say they view their job as taking care of artists’ legacies, not managing their current careers.

What it will mean for the Beach Boys is unclear. Band members — now in their late 70s and early 80s — and others surrounding them mention loose ambitions for television specials, themed restaurants and perhaps a tour tied to the 60th anniversary of their first album. And “Feel Flows” is a reminder of how much Beach Boys history can still be mined to entice audiences that may know the band only from “Surfin’ U.S.A.” and “California Girls.”

Yet despite many statements over the years that old hatchets have been buried — the intraband litigation file goes back decades — the Beach Boys are not quite united. There are still two separate touring units: Love, with Johnston, performs under the Beach Boys name, while Brian Wilson plays with Jardine; both are touring this fall. Just a year ago, Wilson and Jardine supported a boycott after Love’s Beach Boys were booked to perform for a group that supports trophy hunting.

Neither Wilson nor Love see any conflict. “For whatever reason,” Love said, “people will focus on the negative things. But they would be missing the point of the Beach Boys, which is so overwhelmingly positive.”

“To be able to do ‘California Girls,’ ‘I Get Around,’ ‘Fun, Fun, Fun,’ ‘Help Me, Rhonda,’ ‘Surfin’ U.S.A.,’” he added, “all these great tunes, 50, 60 years later, is pretty miraculous.”

Source: Read Full Article