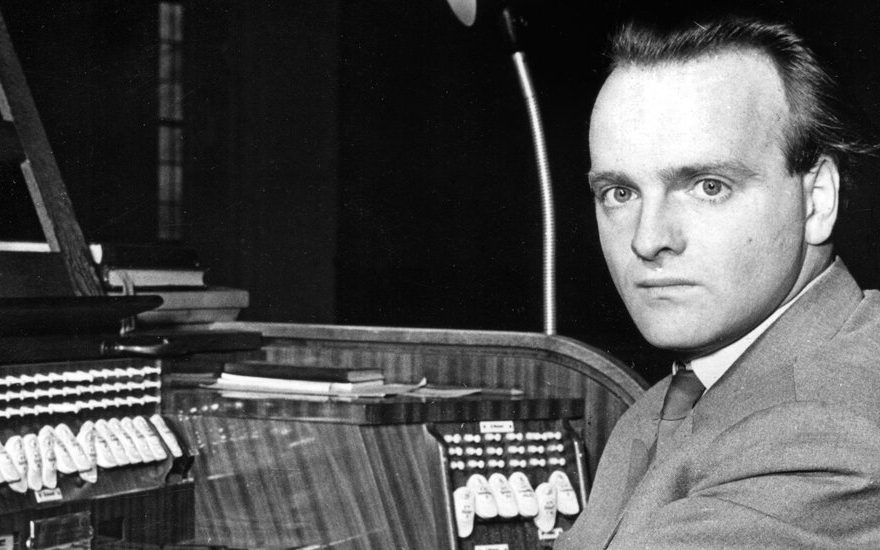

The conductor and keyboardist Karl Richter’s legacy can be explored anew with a 100-disc box set.

By David Allen

It was Karl Richter’s Bach that pushed Nikolaus Harnoncourt over the edge.

Harnoncourt had founded the pioneering period-instrument Concentus Musicus Wien in 1953. But he was still making a living as a modern-instrument cellist in the Vienna Symphony Orchestra in 1969, when Richter conducted him in the “St. Matthew Passion.”

“They think they see the Thomaskantor himself at work,” Harnoncourt wrote in his diary, fuming at the sleepy, ignorant Vienna audience that idolized Richter and referring to the title Bach once held as the choral cantor and director of music at the Thomaskirche in Leipzig.

“Bach-Richter,” Harnoncourt called him — and the name wasn’t inappropriate, so fully had Richter become associated with Bach through dozens of recordings as a conductor, harpsichordist and organist, made primarily for the Archiv imprint of Deutsche Grammophon and now brought together in a 100-disc box set.

Harnoncourt, who transformed the way generations of later listeners heard Baroque music, could not stand this “profound connoisseur of style,” his sarcasm snapping at the work of a man who had himself once been hailed as a revolutionary.

“It has nothing to do with Bach and nothing to do with the Gospel,” wrote Harnoncourt, who died in 2016. “Hardly anyone has the courage to admit that this is nothing they hear here, nothing good and nothing beautiful and nothing moving, just something completely devoid of meaning.”

“A month later I left the orchestra,” Harnoncourt concluded. “I had to.”

Harnoncourt’s caricature was one of many polemics that original-instrument advocates launched to render their forebears — Richter and men more conservative still — almost illegitimate as interpreters of Baroque music. Those polemics worked. The middle of the 20th century — a period of vibrant, competing interpretive traditions — was eventually perceived merely as the last of the “bad old days” of syrupy, hopelessly old-fashioned early-music performance, with Bach and Handel played much the same way as Brahms or Wagner.

“Mr. Richter’s ideas will not strike everyone as the right ones in this day and age,” wrote one New York Times critic in a 1980 review of a “St. Matthew Passion” recording, describing its square phrasing and “plodding” tempos as “decidedly unfashionable if not downright eccentric.” Another wrote, after a B Minor Mass in 1972, that “Mr. Richter’s Bach struck one as essentially outdated, a thinly disguised child of the 19th-century oratorio style.”

But with the period-instrument movement having been, for the most part, victorious, the old arguments have lost their edge. The time is right to listen to Richter again. Peer beyond the polemics, and the Deutsche Grammophon box reveals an interpreter of more than antiquarian interest: a musician of intensity, invention and sincerity — one whose rehabilitation might point the way to a more open atmosphere for the performance of this repertory.

What isn’t in doubt is Richter’s importance in the post-World War II revival of interest in early music. The 100-disc set offers a comprehensive account of his achievement, with Handel, Haydn and even Beethoven framing 64 CDs of Bach, including core works like the Passions; extensive selections of the orchestral, chamber and keyboard works; and a representative survey of the cantatas, offering authoritative singing from the leading vocalists of the time. These recordings were ubiquitous — reference points even for artists who preferred more radical approaches.

“They were the childhood recordings I had,” Julian Wachner, the director of music and the arts at Trinity Wall Street, said in an interview. “If you wanted to hear any kind of encyclopedic collection of Bach, you had to go to Richter. He made us all realize that all of Bach was amazing.”

Born in the Saxon town of Plauen in 1926, Richter laid claim to a performance tradition centered in Leipzig, where he trained as a teenage organ prodigy under Karl Straube and Günther Ramin, two Thomaskantors who held the post that Bach tended from 1723 to 1750. Straube and Ramin, as part of the “objective” spirit that dominated culture in the Weimar Republic, inveighed against expressionism. It was the relatively uncomplicated style that they cultivated — contrived somehow as both new and firmly rooted in tradition — that Richter would later promote worldwide.

“Richter was looking to the immanent qualities of the score as a guide for interpretation — the notion that you pull the expression out of the score, rather than applying the expression to it,” the harpsichordist Mahan Esfahani said. “This sense that the interior laws of music are a language in and of themselves; they don’t need to be ascribed extramusical values.”

After wartime military service for Germany, a spell as a prisoner of war, and the completion of his studies, Richter was appointed organist at the Thomaskirche in 1949, and played when Bach’s remains were reinterred at the church in 1950. Crossing the Iron Curtain for a position at Munich’s St. Mark’s Church in 1951, he founded the Munich Bach Choir and Orchestra in 1954; their promise was sufficient that he declined Leipzig’s entreaties that he inherit the throne of Bach in 1956, when Ramin died.

At a time when artists across Europe were searching for new beginnings in the wreckage of war, Richter’s sincere, straightforward approach to Bach seemed revolutionary, and represented an initial attempt to clear the ground in early music, with instruments like oboes d’amore and violas da gamba peeking through a sound that, while clean, was otherwise lush and familiar.

“When you compare Richter with Furtwängler and Klemperer, in choice of tempos and in terms of relationship to the text, there is a clear desire to present Bach in some kind of objective light, to present this music with no frills, exactly as it was written,” said Bernard Labadie, who applies period practice to modern instruments as principal conductor of the Orchestra of St. Luke’s. These were impulses that Richter’s interpretive successors would claim for themselves.

Seen in hindsight, Richter’s recordings were a hybrid, the product of an approach that stepped away from Romanticism without taking the leap of faith that period scholarship required. While some listeners today struggle with the interpretations — “It’s very difficult for me to listen to what he does for more than 30 seconds,” lamented Labadie — others will appreciate their communicative power.

Richter’s first “St. Matthew Passion” and Mass in B Minor, dating from 1958 and 1961, respectively, have directness and grandeur; his “Christmas Oratorio,” with the peerless singers Gundula Janowitz, Christa Ludwig and Fritz Wunderlich, has never been surpassed; his “Brandenburg” Concertos and Orchestral Suites have a vivacity that defies the stereotypes later pinned to them.

Certainly there are times sluggishness strikes, as in an account of Handel’s “Music for the Royal Fireworks” with the English Chamber Orchestra that is dreary compared to those of contemporaries like Rafael Kubelik and Pierre Boulez. But there are discs, too, when Richter’s approach sweeps all before it, as in his solo harpsichord recordings; or a gripping set of Handel overtures at the helm of the London Philharmonic; or even a brooding “Giulio Cesare” starring Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau and Tatiana Troyanos.

The sense of compromise in some of his orchestral recordings can be hard to shake off; one Times critic called him “the most artful dodger of major issues now before the public.” Setting questions of technique and scholarship aside, there is also an unease, especially in his keyboard performances.

His later organ recordings of Bach, for instance, only sometimes have the imposing force that other interpreters have mustered, though there are thrills — indeed, terrors — to be heard in performances like that of the “Wedge” Fugue, from 1966. There is often a mournful quality to these records, especially the handful he made at the Silbermann organ in Freiburg Cathedral in 1978, an instrument dating from Bach’s time that Richter had played as a small boy.

“It’s very much beneath the surface, but beneath that steeliness there’s something very touching,” Esfahani said. “To be a German, you walked with this mark on your forehead, with this shame. You sometimes think, perhaps, that the patina of objectivity is because this was a society in which you didn’t talk about these things. I don’t want to say there is a dark side, because it suggests that there’s volition on the part of Richter, but there is this deep sadness.”

As the period-practice movement gathered power, this unease grew. Richter’s beliefs were strong enough, at first, to fend off the “purists,” as he called them. He and Harnoncourt both released recordings of the “St. John Passion” in 1965 — Richter with standard forces, Harnoncourt with original instruments and boys in the choir — and it is Richter’s commanding account that sounds fresher and more confident now. But in time, critics detected a loss of purpose.

“It was as if the newer, more modish performance practices had shaken his convictions about his own straightforwardness just enough to undercut his effectiveness,” John Rockwell wrote in The Times in 1980. Richter fought back; scholars, he told Rockwell, “make rules because they have no lives.” But the release that year of his second, starry “St. Matthew Passion” betrayed him, retreating to a self-conscious heft that its predecessor had lacked — to a style closer to the kind he had once deplored.

“You might say that Richter ultimately gets defeated by a movement in which he participated,” Esfahani said. In 1981, he died of a heart attack, just 54.

Site Index

Site Information Navigation

Source: Read Full Article